Kagami Biraki: Making and Breaking Mochi

Kagami mochi, 鏡餠, mirror mochi, with daidai, 橙, bitter orange, ura-jiro, 裏白, back-white, fern, shi-hō beni, 四方紅, four-directions red-edge paper square, displayed on stand san-bō, 三方,three-directions. The sanbō is made of wood and has eight sides, the gi-tchō, 毬杖, ball-hit, is made of wood and has eight sides. The number eight in Japanese Kanji is hachi, 八, which is symbolic of Infinity in Space, radiating outward in all directions.

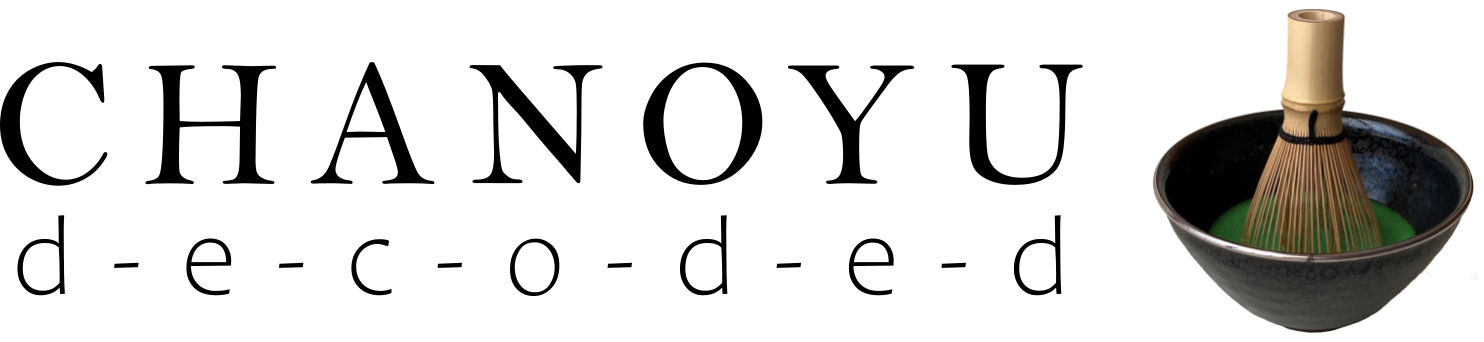

Kō-gō, 香合, incense-gather, called a buri-buri kō-gō, ぶりぶり香合, plump-plump incense-gather. It is made of wood, octagonal in cross-section, tapered at both ends, with a design motif of ‘Taka–sago’, 高砂, High-sand, shō-chiku-bai, 松竹梅, pine-bamboo-prunus, and a married couple, Uba to Jō, 尉と姥, Old Man and Old Woman, on a decorated gold background. The kōgō is modeled after a kine, 杵, mallet, used to make mochi, by pounding mochi-gome, 餠, mochi-rice, in an usu, 臼, mortar, into a sticky mass. The rectangular slot is where a handle would be affixed, and is off-center so that the weight of the mallet keeps the mallet vertical, and is always directed downward.

In the Tearoom for the solar New Year, the kagami mochi may be placed in the tokonoma or another prominent place. Traditionally, the kagami mochi is placed as an offering on the Shintō kami-dana, 神棚, god-shelf, and the Butsu-dan, 仏壇, Buddha-altar. It remains there until the 11th day after the New Year, when it is broken up with a mallet, cooked, and eaten.

The decorative buri-buri kō-gō, ぶりぶり香合, plump-plump incense-gather, is used to hold incense, neri-kō, 練香, knead-incense, to be placed in the hearth for the first sumi-bi, 炭火, charcoal fire, of the New Year. Because the neri-kō is damp, the piece of incense is placed on a tsubaki no ha, 椿の葉, camelia’s-leaf, with both pointed ends cut off. Before the guests look at the kōgō, the leaf is put into the sumi-tori, 炭斗, charcoal-measure.

For the New Year Tea presentation, the buri-buri kō-gō is often displayed in the Tearoom tokonoma after it used when building the first charcoal fire of the solar New Year. It is often displayed with the ha-bōki, 羽箒, feather-brush, which is also used when building the charcoal fire. Decorations and offerings for the New Year includes kagami mochi, 鏡餠, mirror mochi, and in Chanoyu, includes the buri-buri kōgō.

Sumi, 炭, charcoal; ten-zumi, 點炭, offer-charcoal, is the smallest piece of charcoal in the fire in the ro; L. 2 sun kujira-jaku.

Ko-zuchi, 小槌, small mallet, wood, cylindrical head; 2 sun kujira-jaku, and full length; L. 6.2 sun kujira-jaku. The kozuchi is similar to the standard kine mallet.

The mallet used to pound mochi is different from the mallet that is used to break open the hardened kagami mochi, which is called a kine, 杵, pestle. The kine is used to break open the kagami mochi, 鏡餠, mirror mochi, in the procedure called kagami biraki, 鏡開き, mirror open, eleven days after the New Year’s Day, Gan-jitsu, 元日, Origin-day.

On the side of the mallet is a rectangular slot to fit a handle similar to tte slot found on the buri-buri kōgō, however, the sumptuous buri-buri kōgō is not actually used to hit balls, but shows devotion to the New Year celebrations. Traditionally, an octagonal mallet with an offset handle are aspects usually ascribed to the kine which is used to make mochi by pounding steamed mochi rice into a sticky mass. These features present on the gi-tchō, 毬杖, ball-hit, evoke the implement that is used to make mochi, thus, a beginning and an ending.

The Kanji, 毬, iga, ball, burr, of gitchō, refers to a burr or cone of an evergreen, pine, hemlock, etc. Perhaps it may refer more specifically to the matsu-bokkuri, 松毬, pine-cones, that fall from the pine trees around the shrine, like the pine tree illustrated on the buri-buri kōgō. The innate purpose of batting around pine cones is to scatter the seeds within the pine cone. It may also be an aspect of sweeping and cleaning the grounds of the shrine.

In Japan, mochi-tsuki, 餅搗, mochi-pounding, is an important traditional event in preparation for the New Year, from around December 25 to 28. The mochi is made by pounding mochi rice with a kine into a sticky mass in an usu, 臼, mortar, and is formed into two round of different sizes called kagami mochi, 鏡餠, mirror-mochi. The kagami mochi is displayed on a stand, san-bō, 三方 , three-directions, and 三宝, three-treasures, and offered to the god of the New Year.

Pictured above is a child is pounding New Year mochi in an ishi-bachi, 石鉢, stone-bowl; mochi-tsukuri, 餅つき, mochi-making. A heavy wooden mallet, used to pound the mochi, has an offset handle so that the weight keeps the mallet head vertical. The stone bowl is made for pounding mochi is highly refined, and is often placed on a wooden support for stability.

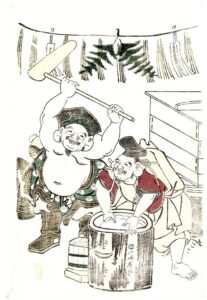

The picture of a chō-zu-bachi, 手水鉢, hand-water-bowl, at the tsukubai, 蹲踞, crouch down, in the ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground, of a Teahouse, is replenished with fresh water before the guests enter the Tearoom. In the ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground, garden, there is a place of purification called a tsukubai, 蹲踞, crouch down. Its principal feature is a stone chōzu-bachi that is filled with fresh water. A wooden hi-shaku, 柄杓, handle-ladle, is used to handle water to purify the hands and mouth before entering the Tearoom. The basin stone is left in its natural state, with a hole carefully carved, or simply hollowed out to hold water. A wooden bucket is sometimes substituted to hold water.

The picture showing a Buddhist priest and a lady burning chasen in a stone basin, which is separate from the chō-zu-bachi. A large stone behind the basin identifies it as a place to sacrifice used tea whisks; cha-sen ku-yō, 茶筅供養, tea-whisk offer-nurture. A stone basin is sometimes used to ritually burn used tea whisks, cha-sen ku-yō, 茶筅供養, tea-whisk offer-nurture. The stone basin may be a natural stone or purposefully created with a bowl for holding the burning whisks.

![]()

Kagami mochi making and breaking is popularly observed on the solar calendar around January 1st, it is important to remember that it traditionally a lunar event, beginning on the first day of the first month of the lunar calendar. The moon played a much stronger role in the past, and was used to determine various when to observe traditional events. The word for the full moon is mochi-tsuki, 望月, full-moon. The Japanese word for pounding mochi in a mortar like the rabbit in the moon, is mochi-tsuki, 餅搗き, mochi-pound.

In Japan, the rabbit is described holding a wooden mallet which he uses to pound mochi (rice cakes) in an usu, or mortar. The mallet and mortar as also visible as dark spots on the moon. In China, the rabbit is believed not to be creating mochi, but is instead mixing the medicine of eternal youth. The myth of the rabbit on the moon is ancient. The earliest written version comes from the Jātaka tales, a 4th century BCE collection of Buddhist legends written in Sanskrit. The legend was brought along with Buddhism from India to China, where it was blended with local folklore. It came to Japan in the 7th century CE from China, where it was again adapted and adjusted to fit local folklore.

The Japanese version of the Sanskrit tale appears in Konjaku Monogatari-shū. A fox, a monkey, and a rabbit were traveling in the mountains when they came across a shabby-looking old man lying along the road. The old man had collapsed from exhaustion while trying to cross the mountains. The three animals felt compassion for the old man, and tried to save him. The monkey gathered fruit and nuts from the trees, the fox gathered fish from the river, and they fed the old man. As hard as he tried, the rabbit, however, could not gather anything of value to give to the old man. Lamenting his uselessness, the rabbit asked the fox and monkey for help in building a fire. When the fire was built, the rabbit leaped into the flames so that his own body could be cooked and eaten by the old man. When the old man saw the rabbit’s act of compassion, he revealed his true form as Taishakuten, one of the lords of Heaven. Taishakuten lifted the rabbit and placed it on the moon, in order that all future generations could be inspired by the rabbit’s compassionate act. It is said that the reason it is sometimes difficult to see the rabbit on the moon is because of the smoke which still billows from the rabbit’s body, masking his form somewhat.

Mochi is part of Japanese cuisine, including a vast variety of ka-shi, 菓子, sweet-of. Such sweets are called mochi, but are made with gyū-hi, 求肥, wish-abundance, a covering made of various rice flours, customarily filled with an, 餡, sweetened bean jam, with various ingredients.

The following is a partial list of variations of mochi and gyūhi:

Hana-bira, 花弁, flower-petal. Dai-fuku, 大福, big-fortune. Uguisu mochi, 鶯, bush warbler. Zen-zai, 善哉, Good-how. Yaki mochi, 焼き餅, toasted-mochi. Kusa mochi, 草餅, grass mochi, mugwort. Tsubaki mochi, 椿餅, camellia leaves. Warabi mochi, 蕨餅, fernbrake mochi. Sakura mochi, 桜餅, cherry mochi. Kashiwa mochi, 柏餅, oak leaf. Tsukimi dango, 月見団子, moon-see round-of. O-hagi, お萩, Hon.-bush clover. Bo-tan mochi, 牡丹餅, male-red mochi. Gin-nan mochi, 銀杏餅, silver-prunus mochi, gingko nut. Yuzu mochi, 柚子餅, citron mochi.

O-sechi ryo-ri, お節料理, hon.-season materials-arrangement (cooking) are foods prepared for the New Year season. Almost every food is readied to eat so that one does not have to ‘cook’ during the holidays. Heating soups and tea are exceptions, as is toasting mochi for o-zō-ni, お雑煮, hon.-miscellaneous-boil, a soup with a myriad of variations, but it must include mochi.

In Buddhism and other beliefs that do not eat any animal flesh, use the multitude of plants of land and sea. The most important ingredient in the soup of ozōni, is a variety of kelp, kon-bu, 昆布, descendant-cloth; any edible species from the family Laminarialean. Konbu, also read kobu, is essential in making da-shi, 出し, extract, stock, which is used in making soups, and the liquid for cooking other foods. In the secular world, dried fish flakes are added to dashi to make the base for soups and used in cooking other foods. Because of the Buddhist vow to not take life, temples often use only konbu and other vegetables to make their dashi. Like many basics, there are as many different ways of making dashi as there are preparers.

One of the important aspects of konbu is the white powder of the leaf’s surface. Some cooks wipe it away, others barely wipe the leaf, because it bears umami flavor. This a type of mildly sweet, natural sugar known as mannitol. Keeping this white substance is desired in the kagami mochi display as it evokes old age. This it also true of the white powder on surface of the hoshi-gaki, 干し柿, dried persimmons, that are part of the mochi display. This is a natural sugar that emerges to the surface, and is called sa-tō no hana, 砂糖の花, sand-sugar’s flower. Again, an emblem of white hair and longevity.

The dried fish flakes are aged prepared filets of katsuo, 鰹, bonito, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, oceanic bonito; victorfish. The Kanji, 鰹, is composed of sakana, 魚, fish, and ken, 堅, firm. The word katsuo implies ‘hard’. The aged and dried, brick-like bonito block is shaved with a plane to make katsuo-bushi, 鰹節, bonito-divide. Freshly shaved katsuo is much preferred over packed shavings. Few people flake their own.

The following is one of the basic ways to prepare plain dashi, 出し, extract:

Dried konbu is put into water. The water is heated. Time passes. The konbu is removed. The dashi is finished. To prepare dashi with katsuo-bushi: to kelp water dashi katsuo-bushi is added, cooked, and strained. The initial dashi is called ichi-ban dashi, 一番出し, one-number extract, which is used in preparation of miso shiru, and other soups, including the ‘hot pot’, which in Japanese is called nabe, 鍋, pot. The used konbu and katsuo are cooked again in water and strained, which is called ni-ban dashi, 二番だし, two-number stock. This niban dashi is used to cook other foods. The cooked konbu is also used in other recipes.

The soup of ozōni is ichi-ban dashi that is made with the konbu that is offered together with the kagami mochi. Although the kaki, persimmon, is one a part of some kagami mochi, modern writers do not mention its fate after the New Year holidays, other than it is eaten.

One of the traditional ingredients of ozōni is some parts of Japan is gobō. Go-bō, 牛蒡, ox-root, Arctium lappa, is the long tap root of a thistle, with sticky burrs. The tough gobō root is eaten to strengthen teeth and chewing muscles. The season for new burdock is early winter from November to January, and it is a good time to eat at the New Year. Burdock root has been used for centuries in Chinese medicine as a ‘tea’ to improve the immune system, lower blood pressure, heal a damaged liver, it is thought that it may prevent or treat cancer, and reverse the signs of aging and improve hair health. It should be drunk with caution. In the Heian period, gobō was regarded as medicine and later as a food vegetable. Gobō is a homonym for go-bō, 御坊, Hon.-quarters, that refers to a Buddhist temple, and a monk’s quarters.

One of the most familiar, some would say necessary, additions to ozōni is the peel of the citrus fruit, yuzu, 柚, citron, Citrus ichangensis x C. reticulata, that has a strong appetizing fragrance. A small piece is added to soup, not just ozōni, and when the lid is raised from the soup bowl, one relishes the scent of the yuzu. Many do not eat the peel. For flavor, color, and texture some green plant is included, such as mitsu-ba, 三つ葉, three-leaves, Japanese parsley, Cryptotaenia japonica. Contains folic acid and ascorbic acid, etc. The greens may be a substitute for the ura-jiro, 裏白, back-white, a kind of fern, Gleichenia japonica, as the unfurled fronds are inedible. Some fern shoots are edible.

In the style of Kan-sai, 関西, Barrier-west, including Kyōto, the ozōni soup includes shiro miso, 白味噌, white flavor-soup, and has maru mochi, 丸餅, round mochi, settled spheres, grilled: the charred surface is greatly enjoyed. In the style of Kan-tō, 関東, including Tōkyō, the ozōni soup is sumashi-jiru, 清し汁, clear-soup, kiri mochi, 切餅, cut mochi, are rectangular blocks that are grilled. Chicken pieces and stock are included in the Kantō-style zōni: the chicken greets the dawn of the New Year.

Mochi is made by pounding steamed mochi-rice into a single mass. Kagami biraki is pounding dry mochi until it is in many pieces. In 15th century Japan, the samurai ceremonially ‘opened’ the kagami mochi with a single strike with a wooden mallet. Others would break it up further to be cooked and eaten. Opening the kagami mochi was accompanied with matches of kendō, judō, jiujitsu, sumo, and other martial and physical arts.

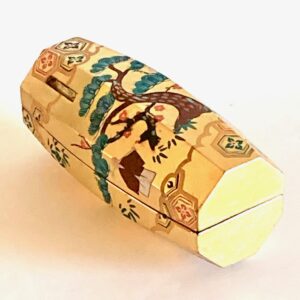

Woodblock print of pounding mochi; Dai-koku, 大黒, Big-black, and E-bi-su, 恵比寿, Bless-like-longevity, mochi-tsuki, 餅搗き, mochi-pounding, by Tama-gawa Shū-chõ, 玉川 舟調, Jewel-river Boat-ready, c.1800.

Daikoku, the god of rice cultivation, pounds the mochi, and Ebisu, the god of fishing, holds the wooden usu, 臼, mortar. They are two of the Shichi-fuku-jin, 七福神, Seven-fortune-gods. Daikoku wields a kine, 杵, pestle, to pound the mochi, rather than his famed ko-zuchi, 小槌, small-mallet, that brings good fortune; which is peeking out from behind him, as is a straw-covered kome–dawara, 米俵, rice-bale.

The mortar is inscribed E-zaki-ya-ban, 江崎屋板, Bay-cape-house-board, the publisher of the print, E-zaki-ya Tatsu-zō, 江崎屋辰蔵, Bay-cape-house-board Dragon-keep; mid-19th century. Daikoku’s garment bears a pattern of multiple hōju.

Rice is steamed in the stack of boxes on the right. The rice-straw shime-nawa, 注連縄, flow-connect-rope, with paper pendants, hemp stalks, and doubled ferns indicate that the scene may be at a shrine to prepare for the New Year. Ferns are a familiar evergreen plant present in the roji garden of the Teahouse. Note the men’s plump earlobes: mochi is kneaded until its density is like one’s mimi-taba, 耳束, ear-lobes. Also, note the mizu-oke, 水桶, water-bucket, near the mortar, which might evoke the te-oke, 手桶, handle-bucket, used to replenish the water of the chōzubachi at the tsukubai.

Tsukubai, 蹲踞, crouch down, in the ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground, of a Teahouse near Gin-kaku-ji, 銀閣寺, Silver-pavilion-temple. The shape of the stone chō-zu-bachi, 手水鉢, hand-water-bowl, may evoke Daikoku’s treasure mallet. Note the ferns.

Steamed mochi rice is put into a stone or wood usu, 臼, mortar, and struck with wood kine, 杵, mallet. First the rice is kneaded with the mallet, and once it sticks together, it is pounded. Another person turns the mass over and over alternating between the pounding. Because the rice is very hot, the mochi turner wets his or her hands in cool water from the teoke before each turning. This also prevents the mochi from sticking to the hands and the mallet. The amount of rice determines the effort put into the pounding. Usually, there is a good deal of strength needed to pound the mochi, which may be one of the intended purposes of pounding mochi. It is a kind of exercise to build up strength and endurance. This endurance building is similar to flying kites in the New Year, to force the flyer to breathe heavily to build up strength in the lungs.

Mochi balls are spherical, and while still soft, settle, remaining round, and it is this reason why it is called kagami, because it is round like ancient bronze mirrors. However, not all ancient bronze mirrors are round. Some mirrors have six or eight sides, some have foliate edges, some are square, etc.

Kagami-biraki, 鏡開, mirror-open, or kagami-wari 鏡割り, mirror-divided, is an annual Japanese New Year event in which kagami mochi rice cakes are offered, sonaeru, 供えた, offer, to the Shintō Toshi-gami, 年神, year-god, and hotoke, 仏, buddhas. The kagami mochi shows people’s gratitude to the gods and Buddha, and prayers for good health. The broken of cut pieces of mochi are cooked and often eaten with shiru-ko, 汁粉, soup-rice flour, with sweetened azuki beans, zō-ni, 雑煮, miscellaneous-boil, soup with boiled or baked mochi, and fire-toasted mochi, etc.

Kagami biraki, 鏡開, mirror-open, also refers to a woman looking at herself in her mirror for the first time in the New Year, hatsu kagami, 初鏡, first mirror. It should be remembered that mirrors in Japan were, and may still be, covered with a cloth, or concealed in a box, and revealed or opened only when needed.

Ken, 乾, Heaven, South

Kon, ☷, 坤, Earth, North

Chawan shōmen, 茶碗, Tea bowl true-face – metal rim seam

Kon, 坤, Earth, North

Ken, ☰, 乾, Heaven, South

Nomi-kuchi, 呑口, Drink-mouth

The chasen is rinsed in the water in a chawan, and raised and lowered three times for inspection. Turning the chasen each time may be associated with the three In, 陰, Yin lines of the Ekikyō trigram for Kon, ☷, 坤, Earth. Straight and curved; dry and wet; horizontal and vertical; Yō and In.

In Chanoyu, a round tray is often purified with the fukusa by wiping the surface with three parallel horizontal strokes. This may be likened to polishing an old mirror. Three horizontal lines may be associated with the three Yō, 陽, Yang lines of Ekikyō trigram for Ken, ☰, 乾, Heaven. Although it is not proscribed, the mound of tea powder poured into the chawan, it is leveled with the chashaku, perhaps drawing the three Yō lines.

The fukusa is used to clean various Tea utensils, and is examined and folded in different ways for particular objects. This is called fukusa sabaki, 帛紗捌きcloth-gauze-handling. Examining its four sides, is called yo-hō-sabaki, 四方捌き, four-direction examine. The Japanese people see the dark configurations on the moon either as a hare pounding mochi or stirring the elixir of life. Because the moon has power over the seas, causing the tides, it is thought that the hare has power over the seas.

Yo-hō, shi-hō, 四方, four-directions; yo-sumi, 四隅, four-corners. Fuku-sa, 帛紗, cloth-gauze, red silk; 9 x 9.5 sun kane-jaku.

The pictured fukusa with horizontal and vertical edges is identified as a square which manifests the aspect of Yō, 陽, Yang, positive, penetrative, male, shin, 真, true. The pictured fukusa turned to form diagonals is identified as a rhombus which manifests the aspect of In, 陰, Yin, negative, receptive, female, gyō, 行, transitional, semi-formal, and sō, 草, grass, informal.

The highly polished surface of the lacquered lid is a mirror, just as the surface of the water within the vessel is also a mirror. When the lid is removed from the mizusashi to have access to the water, it is similar to the kagami biraki of removing the wooden lid of a saka-daru, 酒樽, sake barrel. The undisturbed surface of the sake is also a mirror. The lid of the mizusashi is leaned upright against the side of the vessel. The circular wooden lid of the sake barrel is broken in half with a wooden mallet similar to that of that is used to break open the kagami mochi.

A mirror is silent. The image in the mirror is non-corporeal so that it is incapable of making sound. Sound waves are physical which is In, negative, whereas silence, like thought, is Yō.

Pounding rice with a mallet to make mochi to become kagami mochi makes a repeated thudding sound. The kagami mochi is broken open by pounding it with a mallet and making a repeated thudding noise. When breaking the kagami mochi with a wooden mallet, the mochi is repeatedly struck about every two seconds until the mochi breaks. Much can be learned from children, and how they are instructed in traditional ways of kagami biraki. Those who participate and those who watch, chant encouraging words in time with each strike. The mochi can be extremely hard, and kindergartners are encouraged to try to break the ‘mirror’ exerting much strength. Perhaps this pounding is a kind of physical training.

Kan-shō, 喚鐘, call-bell, green-patinated tetsu, 鉄, iron bell modeled after the bell at Mi-i-dera, 三井寺, Three-well-temple, more formally named On-jō-ji, 園城寺, Garden-palace-temple, Ōtsu-shi.

Bell striker, shu-moku, 撞木, thrust-wood, T-shape bell hammer, kuwa, 桑, mulberry; L. 2.5 sun kujira-jaku, with fiber cord for hanging. The kanshō is rung at night to summon guests back into the Tearoom to have Tea.

Striking the mochi repeatedly to break it open, may be likened to striking the temple bell on New Year’s Eve. The Jō-ya no kane, 除夜の鐘, Remove-night’s bell, is rung hyaku-hachi, 百八, hundred-eight, times to dispel undesirable urges, so that one may attain enlightenment.

Ancient mirrors in Japan, and elsewhere in Asia, are generally round or circular. The water in the chōzubachi when calm becomes a mirror. Before the guests enter the Tearoom from the garden, the tei-shu, 亭主, house-master, replenishes the water in the chōzubachi. First, the teishu dips a ladleful of water from the basin, pours a little into the left hand, switches to the left hand, pours a little onto the right, switches again, pours a little in the clean left hand, sips the water from the hand, and holds the ladle upright so that the remaining water runs down and cleans the handle. Care is taken so that the cleaning water does not fall into the basin.

Purification at the chōzubachi follows a concept of the importance of the number three; the single ladle of water is poured three times: left hand, right hand, mouth, spit – don’t drink water.

The teishu continues to empty the basin with a ladle, and replenishes it with water from a wooden te-oke, 手桶, handle-bucket. The teishu holds the bucket above the empty basin, and pours the water from the bucket so that it refills the basin, makes a refreshing sound heard by the guests who are seated nearby. In a sense, the teishu creates a new ‘mirror’ with fresh water.

The bowl of the chōzubachi is generally circular, and most of the ancient bronze mirrors are circular. When ladling water from the basin, the ‘mirror’ is ‘broken’. The mae-ishi, 前石, fore-stone, of the chōzubachi should have a flat surface as people stand and crouch on the stone to purify the hands and mouth. The underside of the stone can be of any form. There are similar aspects in ancient bronze mirrors that have a flat surface on one side, and the opposite side has relief designs and the knob handle. It is said that at Rikyū’s tea house, Tai-an, 待庵, Wait-hut, the original chōzubachi was named ‘Shiba–yama’ 芝山, Grass-mountain, by Hide-yoshi, 秀吉, Excel-luck.

For further study, see also: Lunar New Year and Kagami Mochi, Sanbō Offering Stand, Year’s End and New Year’s Collection