Kobukusa

A ko-buku-sa, 古帛紗, old-cloth-gauze, also written with Kanji, 古袱紗, is a small square of fine fabric that is used to display or hold a prized Tea utensil. The fabric is doubled, so that it is hemmed on three sides. It is kept in the front folding of the kimono, futokoro or kai, folded in half like a Japanese book, with the fold on the right, together with a folded fuku-sa, 帛紗, cloth-gauze, and folded pack of kai-shi, 懐紙, heart-paper. Because of its kept location, it is also called a kai-chū ko-buku-sa, 懐中古帛紗, heart-middle old-cloth-gauze. The kobukusa is kept in the futokoro, 懐, heart, the front folding of the kimono, together with a fukusa, kaishi, ko-ja-kin, 小茶巾, small-tea-cloth in a small folder. The kobukusa and the kojakin, manifest aspects of In and Yō, the kobukusa is dry, Yō, and the kojakin is wet, In.

The reason that the kobukusa is called ‘old’ fukusa, is because it was formerly the original fukusa, used to purify various utensils. The fukusa was approximately one shaku kane-jaku square of doubled fabric, so that it was necessary to hem the three sides. The width of fabric for fukusa is the same as the width of the woven material, or eight sun kujira-jaku wide, and retains the selvages.

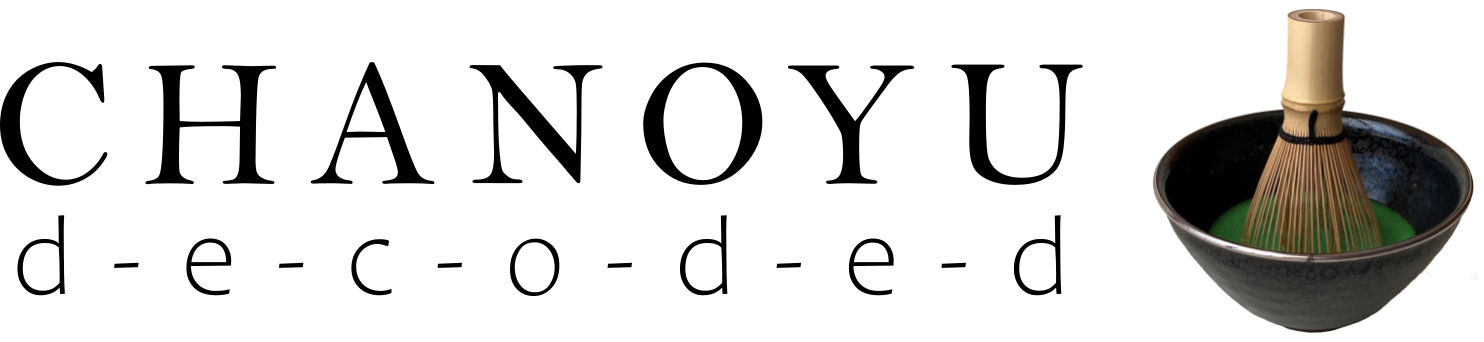

Don-su, 緞子, damask-of, is regarded as the most formal fabric essentially because it is the softest, least abrasive so that it does not damage the object with which it may come in contact. Kin-ran, 金襴, gold-brocade has gold or other metallic thread. Although it may appear that because it has ‘gold’ in it, it would be deemed higher than a simple donsu, the threads may be abrasive. Kan-tō, 間道, interval-way, ordinarily is so-named because it has a pattern that is striped or checked. But, a kantō fabric with stripes, may also have gold thread embroidery, resembles a nishiki, brocade, and is primarily a donsu, so that it is all types. The nishiki, 錦, brocade, is a fabric made of several colored threads in a particular manner of weaving

Kinran may be made of gold thread or narrow strips of paper with gold leaf attached, which is the type on the pictured kobukusa. These strips may be exceedingly narrow as to appear to be threads

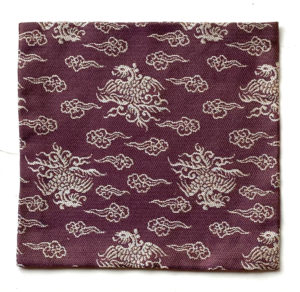

In Asia, the dragon brings rain, and for Buddhists enlightenment. As with many pleasing designs, this pattern is available in many different color combinations.

The pattern is composed of a hare with a sacred pot given by the Buddha and tree in the circle of the moon, with images of a turtle with four written characters on its back. This extraordinary design was taken from a 7th century embroidery that was the earliest mandala in Japan. Several fragments of the weaving are the property of Chū-gū-ji, 中宮寺, Middle-palace-temple, are recognized as National Treasures, and are kept in the treasury of the Shō-sō-in, 正倉院, True-warehouse-sub-temple, in Nara.

There is a little confusion in Japan regarding the rabbit and the hare. The animal is represented by the Kanji usagi, 兎, which refers to the hare, rabbit, coney, etc. The hare is one of the Asian zodiac signs, jū-ni-shi, 十二支, ten-two-branches, and is marked with the Kanji, U, 卯, hare. This sign is identified with the east and the fourth lunar month. In Asia, an image of the rabbit/hare is seen in the configurations on the moon. One tale has the hare pounding mochi. The over-hanging tree is sometimes identified as a katsura, 桂, cinnamon bark tree. Being identified with the moon and helping to cause the tides, the moon rabbit is identified with the west.

In Asian thought, it is believed that the world is supported on the back of a great kame, 亀, turtle (or tortoise). The kame is said to live ten thousand years. The shell of the tortoise was used in divination in ancient China before the creation of the I Ching, 易経, Change Sutra, Japanese Eki-kyō.

A ko-buku-sa, 古帛紗, old-cloth-gauze, is used to support the cha-wan, 茶碗, tea-bowl when drinking koi-cha, 濃茶, thick-tea, from a bowl that is not Raku-yaki, 楽焼, Pleasure-fired. After the teishu places the bowl of koicha out for the guest, the folded kobukusa is placed next to the bowl, with the fold toward the right. Before using the kobukusa, which has been set aside by the guest, the guest tells the teishu that the kobukusa will be borrowed. The guest places the kobukusa on the left hand, and then places the bowl on the kobukusa. This procedure differs from presentation to presentation.

The same designs and patterns can be found in almost all types of fabric. The Japanese Tea connoisseurs appreciated Chinese fabrics and certain patterns, which they adopted and copied. At times, the Japanese version is superior to the Chinese model. Some patterns are associated with Buddhism, and as Tea is closely identified with Buddhism, these motifs are often found in fabrics. One of the most familiar patterns is bo-tan Kara-kusa, 牡丹唐草, male-red Tang-grass, which has flowers amidst scrolling vines. In Chanoyu, these fine and much admired fabrics are used for many purposes, such as kake-mono, 掛物, hang-thing, hanging scrolls.

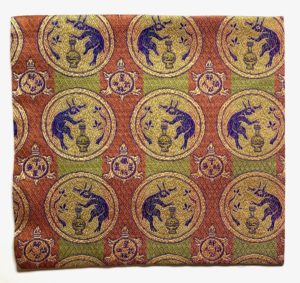

The reverse side of the “Shi-ki Fuku-sa,” 四規帛紗, Four-principles, has the Kanji for Eki, 易, Change, from Rikyū’s name Sō-eki, 宗易, Sect-change. The word eki is part of the Japanese translation of the I Ching, Eki-kyō, 易経, Change-sutra. The area of the Shi-ki Fuku-sa, 四規帛紗, Four-principles, marked with Kanji, Sei, Purity, is where the surface of the fukusa touches the utensil when purifying it in all three ways of folding. This occurs when the fukusa is folded in each of the four styles.

Rikyū’s wife Sō-on, 宗恩, Sect-gratitude, is credited with introducing the plain silk fabric fukusa know today, because she believed that the luxurious fabrics were out of keeping with the austerity and simplicity of Chanoyu. The plain silk fabric of the fukusa is named Shio-ze, 塩瀬, Salt-rapids, ostensibly named for a man who created this particular weaving technique of light warp and heavy weft silk threads.

In time, the size of the kobukusa was made smaller, about one-quarter the size of the full fukusa. This smaller cloth square is called a ko-buku-sa, 古帛紗, old-cloth-gauze, because its fabric was similar to the older fine fabric fukusa. This smaller kobukusa is also called kai-chū kobukusa, 懐中古帛紗, heart-middle old-cloth-gauze, as it is kept in the front folding of the kimono when not in use. This area of the kimono is called futokoro, which is another reading for the character, kai, 懐. The futokoro of a man’s kimono is in front of the belly, whereas the futokoro of a woman’s kimono is in front of the sternum. A Buddhist, before meditation, might put a heated stone wrapped in a towel, and put in the kimono folding near the belly to ward off pangs of hunger. This is the origin of the meal of a Tea ceremony called kai–seki, 懐石, heart-stone: just enough to ward off hunger. So, the futokoro is near the belly.

The two cloths pictured reveal, more or less, hidden aspects, and their relationship. The large dashi-bukusa is used in Yabu-no-uchi, 藪内, Thicket-’s-inside, tradition of Tea, and the small kobukusa is used in the Urasenke tradition. It is apparent that the kobukusa is almost exactly one-quarter the size of the dashi-bukusa. The tradition of Yabunochi, the founder was a contemporary of Rikyū, is for the aristocracy. It may be that the size of their dashi-bukusa, was the model for the smaller kobukusa. It is said that the small kobukusa was created at Urasenke in the period of Yū-myō-sai, 又玅斎, Again-mysterious-abstain, XII, Iemoto, Urasenke, when extravagance was shunned, and that the old large dashi-bukusa, was reduced in size. Notice too, that the pattern of the dashi-bukusa is ‘side-ways,’ which does not bother the Japanese sense of economy and beauty.

A closer look at the large dashi-bukusa reveals that there is a rather wide band of fabric folded and hemmed. The width of one hem along the length is one sun kujira-jaku; the opposite edge hem is .8 sun kujira. When the hem widths are added to the basic width of the fabric, the full width measurement is nine sun kujira-jaku. The number nine is symbolic of the center radiating outward in all directions to infinity. The length of the doubled fabric dashi-bukusa is 8.2 sun kujira, adding two hems, each of .4 sun kujira, which adds .8 sun, the total length of the unfolded fabric is 18 sun kujira-jaku. The number eighteen is double nine, and, perhaps more importantly, is that the number 18 in Kanji is jū-hachi, 十八, ten-eight, which can be written to form the Kanji, ki, 木, wood, that is symbolic of life. Wood or tree, is the only one of the go-gyō, 五行, five-transitions, or elements that grows.

Japanese artists are extremely careful with using fabric resulting in scrupulous use of material when creating a fabric object. Patterns on fabrics are not necessarily ‘matched’ when pieced together, which is a typical Japanese trait and part of their art.

Artists creating and working with fabrics use the kujira-jaku for measurements, so that the original size of the fabric for the fukusa was 8 sun kujira-jaku. Because of the possible confusion between measurements using the kane-jaku and kujira-jaku, the Japanese government decreed that the metric system should be used. Artists to this day continue to use the shaku peculiar to their art, and call it by centimeters. A standard reference to size using the shaku, it is to the kane-jaku. Confusion could reign.

There is no standard size of kobukusa, and different schools of Chanoyu have their own differences. The small kobukusa did not exist in Rikyū’s time, so there are no specifics given by him. Kita-mura Toku-sai, 北村徳齋, North-village Virtue-abstain, are suppliers of fabric objects for Chanoyu, and which are used by Urasenke and others. The fukusa craftspeople at Tokusai determined the size of a kobukusa at 4 x 4.2 sun kujira-jaku, 寸鯨尺, the equivalent of 6 x 6 ¼ inches.

The name and person known as Ya-za-e-mon, 弥左衛門, is also known as Mitsu-da Ya-san-e-mon, 満田弥三右衛門, Full-field Increase-three-right-defend gate. He went to Song Dynasty China, learned a particular weaving craft, and after his return to Japan, started Hakata-ori, 博多織, Esteem-multi-weave. His style of weaving techniques, color contrasts and plain quite color, fine plaids, reflect the influence of the Ming dynasty of China.

In traditional Japan, measurements are determined by using the shaku, 尺, which is divided into 10 sun, 寸, which is divided into 10 bu, 分, which is divided into 10 rin, 厘. The standard measuring device is a narrow ruler made of bamboo of specific length. There is a major consideration however, as there are two lengths of the so-called shaku. They are kane-jaku, 曲尺, bend-measure, which is almost exactly one US linear foot, and kujira-jaku, 鯨尺, whale-measure: flexible whale baleen was used to measure curved surfaces. Japanese weavers and other artists traditionally use kujira-jaku to measure fabrics and objects made of fabrics.

A small kai-chū kobukusa is used to support the Tenmoku jawan in very formal Tea presentations. While the dai is being purified with the fukusa, the Tenmoku bowl should not be put on the floor, so a kobukusa is used. It is apparent that the fabric of the kobukusa should be soft enough to easily conform to the shape of the chawan and the cup-like hōzuki, 鬼灯, demon-lamp, of the dai. A stiff fabric is inappropriate for this use. This is one of the reasons why a donsu, which has a pliant hand, is the most preferred type of fabric for a kobukusa.

Because the kobukusa is so admired, it is for some difficult to fold the kobukusa in half to keep in the front folding of the kimono. So, there are kobukusa that are never folded, but used only to display an object.

The kobukusa presently used by Urasenke is about one-quarter of the standard fuku-sa, 帛紗, cloth-gauze. Sen no Rikyū, 千利休, Thousand Gain-leave, great Tea Master of the 16th century, gave the measurements of the fukusa in one of his Hyaku-shū, 利休百首, Rikyū ’s One-hundred-kind (poems):

帛紗をば竪は九寸よこ巾は八寸八分曲尺にせよ.

Fuku sa wo ba tatsu wa kyū sun yo ko haba wa has sun hachi bu kane jaku ni se yo.

Cloth gauze as for length is nine sun as for width eight sun eight bu bend jaku is.

In Rikyū’s era, the fabric of the fukusa was luxurious, decorative, colorful with gold threads etc. As it was regarded as too fine for humble Tea presentations, Rikyū’s wife, Sōon, created fukusa made of simple plain silk cloth, and reserved the fine fabric fukusa for special occasions and handling fine objects. The large fine fukusa is now often called a dashi buku-sa, 出帛紗, which is put out for the handling or display of an object. In the middle of the 19th century, at the time of Gen-gen-sai, 玄々斎, Mystery-mystery-abstain, XI Head Tea Master of Urasenke, the size of the fine fabric kobukusa was reduced to about one-quarter the size of the large fukusa.

Cha-wan Kazari is a koi-cha ten-mae, 濃茶点前, thick-tea offer-fore, that features special handling of the chawan. In this Tea presentation, Cha-wan Kazari, 茶碗荘, Tea-bowl Dignify, a kobukusa is used to support the chawan, even though the teabowl may be Raku yaki, 楽焼, Pleasure fired, which ordinarily does not require the use of a kobukusa. According to custom, a kobukusa is used when offering tea to a guest, although there are variations. When presenting Tea to a ki-nin, 貴人, noble-person, the chawan is supported on a dai that is modelled after the Tenmoku dai, a kobukusa is not used, even though it may be koicha. This brings into question, what is the actual purpose of the kobukusa? A study of fukusa may give some meaning. The fukusa is examined before purification, and in a very formal presentation, the kobukusa is examined.

The word kazari is usually written with the Kanji, 飾, which means display, ornament, decorate, adorn, embellish, and is often, wrongly used for Kazari tenmae. However, for the Tea presentations the Kanji for kazari is, 荘, which ordinarily refers to a villa, inn, cottage, feudal manor, solemn, dignified manor, house, estate, etc. The Japanese Kanji is altered from the Chinese character, 莊, grassy village, farmstead, hamlet, villa, manor, thoroughfare, main road place of business, shop (gambling) dealer, banker, solemn, serious, etc. The character, 莊, in Japanese means broom. My first apartment in Japan, 1973, was named, Tsuchi-hashi-sō, 土橋荘, Earth-bridge-villa, in Taka-ga-mine, 鷹ヶ峯, Eagle’s Peak, Kyōto.

The kobukusa, as well as the fukusa, is not square. The fabric is doubled, so it is necessary to hem the three edges. The hem is generally 5 bu. Therefore, the 4 x 4.2 sun kujira-jaku kobukusa with three hems of 5 bu began with fabric that is 9 sun x 5 sun kujira-jaku. In traditional Japan, fabric is woven on relatively narrow looms, and weaving is done so that the finished fabric has selvages that are fine enough that they do not need to be removed. Hence, only the cut sides of the fabric need to be hemmed when folded in half and creating a slightly rectangular ‘square.’

Although the looms are narrow, there appears to be no particular standard width. The hemp cha-kin, 茶巾, tea-cloth, fabric is woven at one shaku kane jaku with useable selvages, and is cut to a length of 5 bu and is hemmed on both long sides so that the length is 3.8 sun kujira. Hemp, asa, 麻, is the longest natural fiber, and is without lint. As the chakin is fabric, it is measured with the kujira jaku, and is 8 sun kujira-jaku wide, and the length is 4 sun kujira-jaku. The familiar 8 sun kujira chakin is in fact half the size of the most formal ō-cha-kin, 大茶巾, large-tea-cloth, which is made with one square-shaku of hemp, and is then hemmed on the two cut edges.

The number eight is symbolic of infinity in space, and is thus a potent symbol of eternity. The 8-sun square chakin is symbolically identified with the center of the world and is represented by the character for rice, kome, 米. This character is composed of three characters: hachi jū hachi, 八十八, eight-ten-eight, which manifests the concept of the center of the world.

The origin of this presentation dates to the time of Gen-gen-sai, 玄々斎, Mystery-mystery-abstain, XI, Iemoto, Urasenke. After a Ken-cha, 献茶, Offering-tea, Gengensai received a gift of a bolt of fabric from Kō-mei Ten-nō, 孝明天皇, Filial piety-light Heaven-emperor. Gengensai had made with the material an obi, and shifuku and kobukusa. The shifuku was made to fit a cylindrical shin naka-tsugi, 真中次, true middle-next, tea container. Later, Tan-tan-sai, 淡々斎, Light-light-abstain, XIV, created a gold-lined kuwa naka-tsugi, 桑中次, paulownia middle-node, for the presentation. The original fabric was made of shō-ha ori, 紹巴織, interject-comma weave, which has a very soft hand that requires particularly sensitive handling. The fabric in the pictured set for Wakin presentation is not shōha weave, and so it does not need to be handled in the manner of the Wakin presentation, but is handled in that way that the shōha kobukusa handled. When the guest is looking at the utensils, the guest’s own kobukusa is used to place the lid and the container itself when examining the kobukusa.

The kobukusa is featured in several Tea presentations: Wa-kin, 和巾, Harmony [Japan]-cloth; Dai-en no Shin, 大円之草, Great-circle ’s True, etc. A kobukusa is offered to the guest by the teishu when presenting koicha not using a Raku cha-wan, 楽茶碗, Pleasure tea-bowl. Everyone must have their own kobukusa. A kobukusa is used when presenting Tea with cha-bako, 茶箱, tea-box, which is usucha with chawan. In the elaborate presentation called Shiki-shi Date, 色紙点, color-paper Offer, two kobukusa are presented by the teishu, and Chi-tose Bon, 千歳, Thousand-year Tray, presentation.

Some authorities are puzzled by the look of the ‘tiger’ design, which to others appears to be bamboo leaves with tiger eyes (?). There is a familiar Japanese expression: take ni tora, 竹に虎, bamboo in tiger. This design is available in various styles and color combinations. The chaire shifuku and the kobukusa do not necessarily need to be made of the same fabric for the Tea presentation of Chaire Kazari. Note in the picture above, the subtle ridge of the fabric of the turned-in hem. The primary fold of the doubled fabric kobukusa is on the right side.

The area of Tanba, northwestern Kyōto Prefecture, is famous for its ceramics, chestnuts, fine cotton fabrics, and other specialties. The pictured kobukusa was from a women’s obi, for a friend, who then gave it to me. The preferred and perhaps ideal kobukusa is made of silk, however, a prized possession can be used if it serves the purpose. The relationship between the kōgō and the kobukusa is in harmony with the wabi, 侘, esthetic of Chanoyu.

It is curious that the Kanji for fuku, 帛, in the word fukusa, 帛紗, is composed of white, haku, 白, and cloth, kin, 巾, which could be applied to the chakin as it is a white cloth. However, the color of the true fukusa is made of white silk, that is used in Ken-cha-shiki, 献茶式, Offering-tea-rite. Another reading for the Kanji fuku, 帛, is kinu, which is synonymous with ‘silk,’ and most fukusa are made of silk, and written with the Kanji, 絹, that is read kinu. Japanese fabric objects that predate those used in Chanoyu include those used in serving meals in Buddhist temples called Ō-ryō-ki, 応量器, accept-amount-utensil.

For further study, see also: Eight-Ten: Fukusa, Kobukusa and Mandala Part 1, Kobukusa and Mandala Part 2, Kobukusa Origins, and Kobukusa Picture Gallery