Tea in November

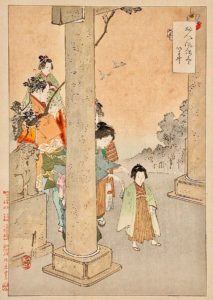

Perhaps the most outstanding event in Japan in November is Shichi-go-san, 七五三, Seven-five-three, when children of those ages are taken to Shintō shrines for prayers and blessings on November 15. In the world of Chanoyu, the most important event is Sō-tan-ki, 宗旦忌, Sect-dawn-memorial, which is held on November 19.

The boy is shown stepping through the tori-i, 鳥居, bird-reside, gate, into the sacred space, correctly, with his left foot, in this print with its extraordinarily ‘Japanese’ composition. Coaxed by his mother, perhaps, she carries a bag containing talismans, which are offered by the shrine, and thereby implying that it is the occasion of Shichi Go San festival.

Children are brought to the Shintō shrine for blessings, and especially for girls who are ages 3 and 7 and boys of age 5. One of Japan’s great desires is in the expression, ‘ichi hime ni tarō’, 一姫二太郎, one princess two great-son. This is the order in which a family wants to have children; a girl is first so that she can take care of her brother who is the next born son. Tarō refers to the first son.

The original candy was ko-haku, 紅白, red-white, with designs of the Kanji, kotobuki, 寿, longevity, in red / pink candy, and the face of Kin-ta-rō, 金太郎, Gold-great-boy, in white candy. These sweets were sold during Shichigosan at Sen-sō-ji, 浅草寺, Shallow-grass-temple, also called Asa-kusa Kan-non, 浅草観音, Shallow-grass See-sound, where the sacred deity is Kannon. The custom of selling chitoseame at temples and shrines spread throughout the country. The candy and other treats and talismans are offered in long paper bags labelled, Chitose Ame.

Hundreds of Urasenke followers gather on November 19th at Konnichian to observe the memory of Sōtan. Various Tea presentations including Ka-getsu, 花月, Flower-moon, are offered.

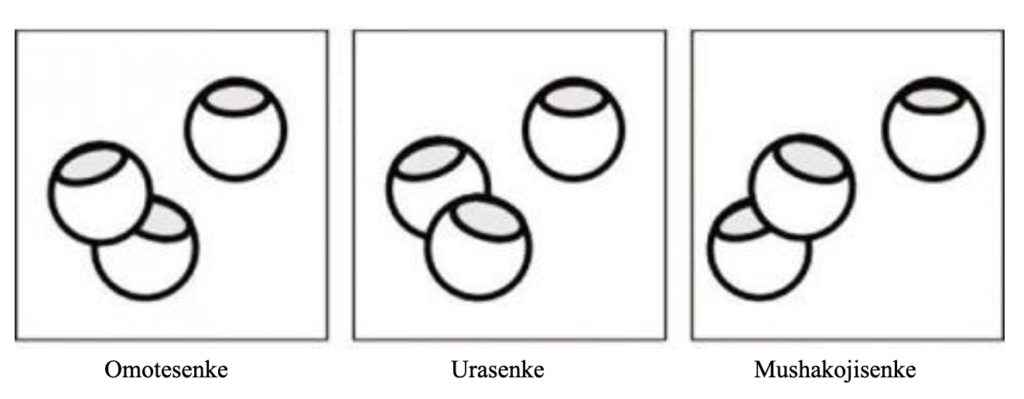

Sen Sō-tan, 千宗旦, Thousand Sect-dawn: 1578年2月7日(天正6年1月1日)- 1658年12月19日(万治元年11月19日)He was the grandson of Sen no Rikyū, it, and was the founder of the San-Sen-ke, 三千家, Three-Thousand-families: Omote-sen-ke, 表千家, Front-thousand-family, Ura-sen-ke, 裏千家, Inner-thousand-family, and Mu-sha-kōji-sen-ke, 武者小路, War-rior-little-way-thousand-family. He is lovingly called Gen-paku, 元伯, Origin-uncle.

Sōtan created various crests for his families. He acquired a den-bō, 田宝, rice field-treasure, that is more commonly called mizu-tama at ancient shrine of Fushi-mi Ina-ri, 伏見稲荷, Down-look Rice plant-carry. The denbō was made of the earth around the shrine dedicated to the god of rice. For the crest, he used three jars, removed the pointed lids, and arranged them differently for each of his three families, and the designs were called the tsubo-tsubo-mon, ツボツボ紋, jar-jar-crest. The three lids became the model for the crest worn by each of the family’s iemoto, the ko-ma mon, 独楽紋, solitary-pleasure (child’s top) crest.

When Sōtan retired, he lived with his young son So-shitsu, 宗室, Sect-room, in the back part of the family estate. He built Kan-un-tei, 寒雲亭, Cold-cloud-house, which is an eight-mat room that opens wide onto a garden. Later, he built a hut that has an interior of two tatami, however it is an ichi-jō dai-me, 一畳台目, one-mat support-eye, that has a board that fills the empty space of the daime. To inaugurate the opening of his Tea hut, he invited various abbots, one at a sitting, as there is space for only two persons.

One of the invited abbots did not arrive at the appointed time. Believing that his guest could not come for Tea, he left a note bidding him coming another day. The guest, Sei-gan O-shō, 清巌和尚, Pure-cliff Harmony-esteem, the abbot of Dai-toku-ji, 大徳寺, Great-virtue-temple, arrived, and unable to find Sōtan, also left a note stating that for a lazy monk there is only today, kon-nichi, 今日, now-day. Thereafter, Sōtan called his home, Kon-nichi-an, 今日庵, Now-day-hut, which identifies Urasenke to this day. The Kanji, 今日, are also, more commonly, read kyō.

Knowing the difficulties that his grandfather, Rikyū, had with the aristocracy, Sōtan chose to avoid such involvement, much to the dismay of some wealthy followers. Sōtan was modest and humble, and accompanied Rikyū on many occasions. He was the Tea teacher of empress consort, Tō-fuku-mon-in, 東福門院, East-fortune-gate-institute. In life, he was called wabi Sōtan, 侘, humble Sōtan, preferring the simple things. However, as Tea teacher to the imperial empress consort, a Tokugawa, and her court, he had red chakin to conceal the rouge worn by the ladies. He also created a ro-buchi, 炉縁, hearth-frame, decorated with the gorgeous color and gold lacquer pattern of hana ikada maki-e, 花筏蒔絵, flower-raft embed-picture.

Sen-sō Sō-shitsu, 仙叟宗室, Hermit-elder Sect-room, was the fourth son of Sōtan. He went to Kana-zawa, 金沢, Gold-swamp, to aid in the establishment of Chanoyu under the aegis of Mae-da-ke, 前田家, Fore-field-family. Among the artists who gathered in Kanazawa was Chō-za-e-mon, 長左衛門, Long-left-defend-gate, a disciple of Raku Ichi-nyū, 楽一入, Pleasure One-enter, IV, who sought suitable clay, and settled in a suburb called Ō-hi, 大樋, Great-trough, which he took as the pottery’s name. The actual family name is Nara. Sensō Sōshitsu returned to Kyōto, and became the first generation Iemoto of Urasenke.

Kake-jiku, 掛軸, hang-scroll; calligraphy, Hi-bi kore kō-jitsu, 日々是好日, Day-day is good-day. Buddhist read, nichi nichi kore kō nichi. Chinese: ri ri shi hao ri and jih jih shih hao jih.

Calligraphy by Ō-nishi Ryō-kei, 大西良慶, Great-west Good-delight, 1875-1983, chief priest of Kiyo-mizu-dera, 清水寺, Pure-water-temple, Kyōto.

Born in Nara in 1875, died in 1983. Signed at left, Kiyo mizu dera hon zon ryō kei, with red stamp, 清水寺本尊良慶, Pure water temple true lord Good-delight, Ichi-mon-ji, 一文字, one-letter-character, and fū-tai, 風帯, wind strap, Kara-kusa kin-ran, 唐草, Tang-grass gold-brocade, on white cloth. Chū-mawashi, 中廻し, middle-surround – blue don-su, 緞子, damask-of. Ten-chi, 天地, heaven-earth, brown silk. Jiku, 軸, scroll, black-lacquered wood.

Length: 5.28 shaku kane-jaku, 63 inches – 160.5 cm. Width: 1 shaku kane-jaku. With box made of momi, 樅, fir.

The expression is included in the Heki-gan-roku, 碧巌録, Blue-cliff-record. Case 6: Yun-men’s ‘Good Day’, Yun-men, 雲門, Cloud-gate, giving instructions, said “I don’t ask you about before the fifteenth day; bring me a phrase about after the fifteenth day.” Yun-men himself answered instead of the monks, “Every day is a good day.” The great Chinese Zen priest, Yun-men, Cloud-gate, (864? – 949). In Japanese he is called Unmon.

Ōnishi Ryōkei was one of the most important and colorful Buddhist priests of the 20th century. For years he lived as a semi-hermit in the mountains of Kyōto while serving as abbot of Kiyomizu-dera, which is perhaps the most famous temple in Japan. Ryōkei each day commuted miles on foot to Kiyomizu. He was an outstanding scholar, an excellent artist, and a stimulating speaker. In his late 80’s Ryōkei surprised everyone by marrying a young woman and promptly fathering two children. Ryōkei remained active right up to his death in 1983 at the age of 108. 108 is an extraordinarily important number especially in Buddhism. The number 18 is symbolic of life, and the number 6 is symbolic of the Infinity in Time: 18 x 6 = 108 – hyaku-hachi, 百八.

Sōtan maru-joku, 丸卓, round-stand; round, black lacquered display stand with thick baseboard, ji-ita, 地板, earth-board, and upper shelf, ten-ita, 天板, heaven-board, raised on two slightly curved wide splats, and a small wooden bracket stabilizes the shelf to the splats. The surface has, variously, soft, shallow grooves, and some wider and more prominent, parallel to the shō-men, 正面, correct-face. The tana is essentially round, which is In, 陰, negative, receptive, however, the faceted surface of the baseboard make it Yō, 陽, positive, penetrative.

The height is 13.5 sun kane-jaku, diam. or 10 sun kane-jaku. The width of each splat is 1.875 sun kane-jaku. Transposed to kujira-jaku, the height 10.8 sun kujira, the diameter is 8 sun kujira, and the splat width is 1.5 sun kujira. The width of each facet of the baseboard is 8 bu kujira-jaku, and there are 15 exposed facets on each side, which adds to 30 facets. The four facets next to and slightly covered by the splat are 7 bu kujira wide.

Because of the partially hidden facets, the total number of facets is approximately 31.3. This appears to be a strange number outside of the more familiar and symbolic numbers associated with Chanoyu. However, it is very close to san-ju-san, 三十三, three-ten-three, which is the number of manifestations of Kannon, the Buddhist goddess of mercy. Given the profoundly symbolic numbers of 108 and 8, it is possible that 31.3 may actually be identified with Kannon.

The maru-joku is a tana, 棚, shelf, but it is also called a joku, 卓. A joku is a display stand that has a specific purpose, but is used in a different situation, and is called a joku. Sōtan’s maru-joku was once a saka-daru, 酒樽, sake-barrel, that he found in the O-gawa, 小川, Little-river, in front of his home in Kyōto.

Sake barrels were and are most often made of sugi, 杉, cedar. The flat facets of the base board emulate the wooden staves of the barrel. Modern sake barrels are made in three standard sizes: H. 40, 50, and 60 centimeters, with the same diameters. Sake barrels taper outward from the bottom to the top, whereas the Maru-joku is essentially cylindrical with a constant diameter.

Sōtan used the barrel as a tana in the Tea room, and in time had Hi-ki I-kkan, 飛来一閑, Fly-come One-lazy, lacquer it black. The style of lacquer applied to Sōtan’s barrel is called I-kkan-bari, 一閑張り, one-lazy-stretch, named after the artist. Ikkan-bari is made of layers of paper and lacquer. The Hiki family, in its 16th generation, in 2022, is one of the Sen-ke Ji-sshoku, 千家十職, Thousand-family ten-work, ten families of artists and craftsmen who supply utensils and objects to the Sen families. Sōtan’s maru-joku has been copied endlessly, and some versions are kumi-tate, 組み立て, construct-stand, and can be disassembled.

The Ogawa exists in name only, and is part of the address of Urasenke, O-gawa-dōri, 小川通, Small-river-street. A small part of its riverbed directly in front of Urasenke’s Kabuto mon, 兜門, Helmet gate, has been kept with two stone bridges leading from O-gawa-dōri, 小川通, Small-river-street, to the grounds of Hon-pō-ji, 本法寺, True-law-temple, and a way to Urasenke properties. The riverbed has been planted with azaleas and other plants and trees.

The kama in the ro should place the hane, 羽, wing, the curved flange where the top of the kama joins at the bottom, a little above the top of the rodan. This is also true with a kama that does not have a hane, which is called ha-ochi, 羽落ち, but has a rough surface at the seam of the kama top and bottom.

Ro gama, 炉釜, hearth kettle; tetsu, 鉄, iron, in the form named Amida-dō, 阿弥陀堂釜, Praise-increase-steep-hall kettle. Note the ha-ochi, 羽落ち, wing-drop, around the lower middle of the kama suggesting that there had been a hane, 羽, wing, to support the kama on the upright collar rim of a kiri-kake bu-ro, 切掛風炉, cut-hang wind-hearth. A shin nari gama, 真形釜, true-form kettle, ideally, should have a hane.

Kazari hi-bashi, 飾火箸, display fire-rods; square-section copper, with scored lines of shichi go san, 七五三, seven five three, with silver alloy gin-nan gashira, 銀杏頭, silver-apricot head, by Ki-mura Sei-sai, 木村清斎, Tree-town Pure-abstain, L. 9.6 sun kane-jaku, shaft 9 sun kane-jaku. Choice of Hō-un-sai, 鵬雲斎, ‘Phoenix’-cloud-abstain.

It is said that the Shichi Go San festival started on the 15th day of the 11th month of the lunar calendar in 1681, to pray for the health of Tokugawa Tokumatsu, the lord of Tatebayashi Castle.

Uneven numbers are unlucky, so that calendar dates such as 3, 5, 7, etc. need protection that is in the form of matsuri, 祭, festivals. The 11th month of the lunar calendar is a month to give thanks to the gods for the year’s harvest, and the 15th day of the lunar calendar is of course the full moon. In modern times, Shichigosan has been held on November 15th.

Sōtan is very closely connected to the ginkgo, i-chō, 銀杏, silver-apricot. Ginkgo nuts are abundant and ripe in November. Followers of Urasenke do not eat them until Sōtanki when they are included in gin-nan mochi, 銀杏餅, silver-apricot mochi. Ginnan mochi are made annually for Urasenke by the celebrated and ancient company of Kawa-bata Dō-ki, 川端道喜, River-edge Way-joy.

In the garden of Urasenke is a ginkgo tree that was planted by Sōtan, and in the great fire in the summer of 1730, liquid rained down from the tree, and protected Sōtan’s Yū-in, 又隠, Again-retire, Tea hut. The ginkgo leaf is an emblem of Urasenke. It is believed that the ginkgo tree has been on the earth for more than 150 million years.

For Robiraki, rips, holes, damaged, and stained shō-ji gami , 障子紙, hinder-of paper, should be repaired. Old dead bamboo fence posts renewed with ao-dake, 青竹, green bamboo. In an ideal world, the shōji gami should be renewed for the new year. The bamboo fence should be made anew with green bamboo for the New Year. The roji garden bamboo gate of the chū-mon, should be made anew for the New Year.

Throughout the year, small holes in the shōji paper may be covered with a piece of the same paper cut in the form of a maple leaf or a flower blossom. As these are inappropriate for the Tearoom, it is proper to re-paper the full square of the shōji.

The present (2022) Iemoto of the family is Ō-hi Toshi-o, 大樋年雄, Great-trough Year-male, Chō-za-e-mon XI, 長左衛門XI, Long-left-defend-gate 11. I had the great honor of teaching Chanoyu to Toshio San when he was a student at Boston University, many years ago, and we have remained friends. As in most traditional families, the heir takes the same name with a number signifying the generation as iemoto.

Cha-shaku, 茶杓, tea-scoop; bamboo naka-bushi, 中節, middle-node, by Kage-bayashi Sō-toku, 影林宗篤, Shadow-grove Sect-kind; L. 6 sun kane-jaku, named ‘Hō-rai’, 蓬莱, Mugwort-goosefoot, Matsu-naga Gō-zan, 松長剛山, Pine-long Strong-mountain, abbot of Kō-tō-in, 高桐院, High-paulownia-sub temple, Dai-toku-ji, 大徳寺, Great-virtue-temple, Kyōto.

Tomo zutsu, 共筒, self-tube, bamboo, inscribed Hō rai, Mugwort goosefoot, with the abbot’s ka-ō, 花押, flower-seal, a stylized number of his generation as abbot.

Box lid inscribed from the top; mei, 銘, inscription, Hōrai, 蓬莱, Mugwort-goosefoot, Murasaki-no, 紫野, Purple-field (area of Daitokuji), Kō-tō, 高桐, High-paulownia, Gō-zan, 剛山, Strong-mountain.

Kōtōin is the mortuary temple of the Hoso-kawa, 細川, Narrow-river, family, and Hosokawa Tada–oki, 忠興, Loyal-entertain, known as San-sai, 三斎, Three-abstain, was a close follower of Sen Rikyū. Sansai’s wife, ガラシャ, Gracia, was a Christian and the daughter of the traitor, Akechi Mitsu-hide, 明智光秀, Bright-wisdom Light-excel, who attempted to overthrow the government of O-da Nobu-naga, 織田信長, Weave-ricefield Faith-long.

The Tearoom, Hō-rai, 蓬莱, Mugwort-goosefoot, Kō-tō-in, 高桐院, High-paulownia-sub temple, Dai-toku-ji, 大徳寺, Great-virtue-temple, Kyōto. The alcove is a ge-za doko, 下座床, down-seat-floor, with the toko–bashira, 床柱, floor-post, and flowers are on the right side. The low shelf on the left is a tsuke-sho-in, 付書院, attach-write-institution, which is for unrolling scrolls, and in a Buddhist environment, the scrolls are religious texts.

The Hōrai Tea room at Kōtōin was once a part of the residence of Take-no Jō-ō, 武野紹鴎, War-field Help-gull (1502-1555). The room is in the manner of En-nō-sai, 圓能斎, Circle-art-abstain, XIII, Iemoto, Urasenke, Kyōto. Primarily, Hōrai is the island home of the Immortal Sages and the Shichi-fuku-jin, 七福神, Seven-fortune-gods. The name of the Tea room refers to mugwort and goosefoot have been beneficial herbs in Asia for centuries.

Among those were buried at Kōtōin include Sei-gan O-shō, 清巌和尚, Pure-cliff Harmony-esteem, the abbot of Dai-toku-ji, 大徳寺, Great-virtue-temple. Sōtan trained in Rinzai Zen Buddhism with Seigan, who contributed somewhat unintentionally to prompt Sōtan to name his Tearoom, ‘Kon-ni-chi-an’, 今日庵, Now-day-hut.

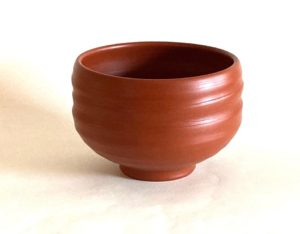

Left; chawan, side view showing low ring foot. Right: chawan bottom showing irregular ring foot and unglazed ‘square’ tsuchi-mi, 土見, earth-see. When using a chawan to serve koi-cha, 濃茶, thick-tea, that is not Raku yaki, 楽焼, Pleasure fired, such as the Seto yaki bowl pictured above, a ko-buku-sa, 古帛紗, old-cloth-gauze is required to support the bowl.

The name of the chawan, Amida, was given after my return visit to Japan in search of a figure of Amida. Living in Boston following more than four years in Japan, I longed for the peace I gained from seeing the tranquil faces of Buddhist sculptures, particularly, Amida. In Kyōto, having searched in vain in countless shops for such a figure, the Seto chawan at an antique shop seemed a superb alternative. I acquired it, and named the chawan ‘Amida’. Back in Boston a year or so after, a figure of Amida did come into my home to bless it and my Garandō Tea room.

The image is called the Kuro-hon-zon, 黒本尊, Black-main-lord, named for the devotional incense smoke that darkened the figure over many years. The figure, worshipped by Tokugawa Ieyasu, is kept in an enclosed shrine, and revealed to the public only three times a year.

Tokoname is one of Japan’s historically renown Ro-kko-yō, 六古窯, Six-ancient-kilns. The chawan was a gift from Keiko Fukuhara Thayer, whose husband, John, was born in an I-doshi, 亥年, Boar-year. John E. Thayer III, a devoted scholar of Japanese culture, was one of my dearest mentors.