Tea and the Sōrin

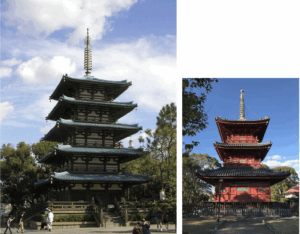

One of the most visually distinct forms of architecture in Japan is the pagoda. Atop the structure is a nine-tiered spire called the sō-rin, 相輪, mutual-ring. The sōrin is rich with symbolic meaning both in Buddhism and Shintō. This symbolism is evoked in the Tea garden, the Tea house, and the tools used to present Tea.

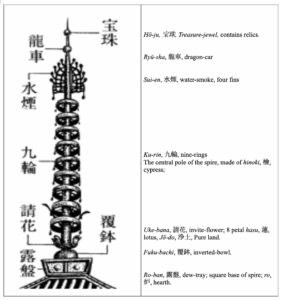

The spire, sō-rin, 相輪, together-ring, is a feature of the five-storied pagoda, go-jū-no-tō, 五重塔, five-tier-’s-tower, and san-jū-no- tō, 三重塔, three-tier-’s-tower. The sōrin is composed of many aspects, here, the upper-most component of the spire is the focus as it relates to architecture, philosophy and Tea.

The hōju at the top of the spire has been used to represent the house of the Buddha’s relics since ancient times, and is enshrined at the very tip of the tower as a symbol of the brilliance of Buddha. The ryū-sha, 竜車, dragon-carriage, is located between the hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel, and the sui-en, 水煙, water-smoke, and is said to represent the vehicle of the divine, which in modern sensibility, equates to the emperor, or a person of nobility.

In a traditional spiritual context, derived from Vedic tradition, the vehicle of the divine is called kundalini – the vehicle for self-realization. The etymology of kundalini has its root in the Sanskrit word, kundala, which means coiled or circular. Dormant kundalini is represented as a coiled snake at the base of the spine. Once activated, kundalini can be described as awakening the dragon.

The dragon is a universal symbol for immense strength, wisdom, and animating spirit. Therefore, “kundalini dragon” symbolizes the awakening and rising of this dormant, life-giving energy through spiritual practices which lead to transformation and enlightenment. This is manifest in the ryū-sha, 竜車, dragon-vehicle. Ryū, also known as a naga, 竜, is semi-divine human-cobra chimera in Hindu and Buddhist mythology

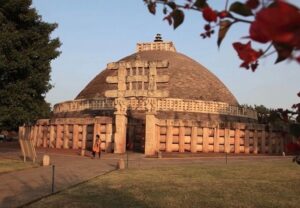

The structure of the pagoda is likely based on renditions of traditional stupa found in India and Southeast Asia. The stupa (heap) is a sacred monument that enshrines the Buddha’s remains. It symbolizes his enlightened mind and wisdom, and serves as a visual and spiritual reminder of the path to enlightenment.

Atop the brick dome, anda, is a square balustrade called a harmika, surrounding a chattra, three-tier umbrella. The structure of the harmika resembles the origin of the ro-ban, 露盤, dew-pan, of the Buddhist spire. The etymology of harmika, house, suggests the abode of the gods, separating the sacred and and physical realms.

Stupas are often visited for meditation and ritual practices. Stupa in Japanese is so-tō-ba, 卒塔婆, die-tower-nurse, which is the structure that became the Go-rin-tō, 五輪塔, Five-ring-tower.

The transition of the gorintō form as it can be seen in stone lanterns and traidional architecure.

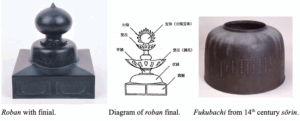

The ro-ban, 露盤, dew-pan, and hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel, are features adapted from the sō-rin, 相輪, phase-ring, spire on the roofs of Japanese pagoda, and other structures. It is present on some the pyramidal roof of Buddhist architecture in Japan. The most frequent is the roof of the kyō-zō, 経蔵, sutra-treasury, the library of Buddhist documents.

A roban atop a kyōzō, three-foot dew plate with bronze finish.

There are aspects of the sōrin that have inspired or been made as part of other objects.The Buddhist architectural feature of the fuku-bachi, 伏鉢, inverted-bowl, predates the chawan and the kama.

The ro-ban, 露盤, dew-tub, is the base of a pagoda finial. With square roofs, that is, square, six-point, and eight-point roofs, something needs to be placed at the top of the roof where the corner ridges meet to protect it from rain. For this purpose, a dew pan was invented, and it is made of stone, copper, tiles, etc. Older roofs are simple and undecorated, but later ones that also serve as decorations began to be made. Broadly speaking, the roban can be divided into two types based on shape: the jewel dew pan, and the flaming jewel dew pan.

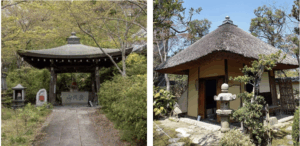

Left: purification basin, chō-zu-ya, 手水舍, hand-water-house, at Minami-Ho-kke-ji , 南法華寺, South-law-flower-temple, at Tsubo-saka-san, 壺阪山, Jar-slope-mountain, Nara. The pyramidal roof is crowned with a ro-ban, 露盤, dew-pan, and hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel.

Right: sō-an cha-shitsu, 草庵茶室, grass-hut tea-room, with pyramidal, thatched roof crowned with roban and hōju. Both structures have relatively permanent vessels of water. There is everpresent cool water at the house of worship, and evanescent hot water in the secular tea house.

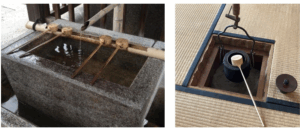

Left: te-mizu bachi, 手水鉢, hand-water bowl, with several hi-shaku, 柄杓, handle-ladles; stone basin with water for purification at a temple. Note bamboo spout.

Right: ro, 炉, hearth, sunken hearth in a tea room – copper ro-dan, 炉壇, hearth-foundation, with wood ro-buchi, 炉縁, hearth-frame. With iron tsuri-gama, 釣釜, suspended-kettle, with bamboo, ji-zai, 自在, self-exist, and hishaku.

For purification before worshipping at a temple or shrine, several people use multiple ladles to handle the fresh water at the basin. Whereas, the host of a Tea gathering uses a single ladle to handle hot water to make tea.

When preparing tea, the host wrings both hands together is an act called shiba chō-zu, 芝手水, grass hand-water. Buddhists clean their hands by rubbing them with dew-laden grasses. Basins for chōzu are an essential aspect of approaches to temples and shrines to utilize before worshipping, are also called chō-zu-ya, 手水舍, hand-water-house. The chō-zu–bachi, 手水鉢, hand-water, is the central feature of the tsukubai, 蹲踞 crouch-down, in the tea garden, ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground. In Buddhism, ro, 露, dew, means enlightenment.

The pyramidal roof of a thatched tea hut at times is covered with a large inverted bowl. Sō-an cha-shitsu, 草庵茶室, grass-hut tea-room, thatched Roof Teahouse, I-hō-an, 遺芳庵, Linger-fragrance-hut, located at Kō-dai-ji, 高台寺a, Hight-support-temple, Kyōto. The large circular window is called the Yoshi-no mado, 吉野窓, Lucky-field window, because it was favored by Yoshino Ta-yu, 吉野太夫, Grand-spouse.

Rikyū had a chawan made that was modeled on the Amida-dō gama, 阿弥陀堂釜, Praise-increase-steep-hall kettle. Chōjirō’s chawan named Oguro is a Raku example. Rikyū also has a square chawan made modeled on a square kama. However, there is the question of what was the model for the Amida-dō gama The Daitenmoku chawan was inspired by the Go-jū-no-tō, 五重塔, Five-tier ’s tower, which in turn was modeled after the Go-rin-tō, 五輪塔, Five-ring-tower, and the spire on the top of the pagoda: sō-rin, 相輪, gather-ring.

Another way the chawan can be seen in relation to the aspects of the sōrin is by looking at the similarities pictured below

Left: fuku-bachi, 伏鉢, inverted-bowl; according to an inscription carved on the surface of the fukubachi, the temple was built in 689, during the reign of Empress Jitō.

Center: modern fuku-bachi and parts of sōrin, spire, including the uke-bana, 受花, invite-flower, polished brass.

Right: ten-moku cha-wan, 天目茶碗, Heaven-eye tea-bowl, ceramic with metal fuku-rin, 覆輪, overturn-ring, and dai, 台, support, with adorned, wooden hane, 羽, wing, with five petals, Ainu craft.

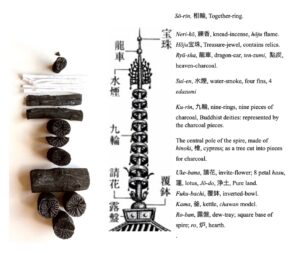

Perhaps the charcoal and incense in the ro are symbolic of the Sō-rin, 相輪, 相輪, Together-rings, spire on the top of a Go-jū-no-tō, 五重の塔, Five-tier-’s-tower, a reliquary for the Buddha’s remains.

Left: pieces of charcoal, white branch charcoal, and a neri-ko tetrahedron used with the ro, 炉, hearth.

Right: spire of Buddhist pagoda, sō-rin, 相輪, mutual-ring, with ku-rin, 九輪, nine-rings.

Three pieces of charcoal are set afire and placed in the furo together called shita-bi, 下火, base-fire. When building the charcoal fire in the presence of the guests, additional pieces of charcoal are added to the shitabi.

The two twigs of the eda-zumi, 枝炭, branch-charcoal, may represent the four-part sui-en, 水煙, water-smoke.

The smallest piece of charcoal, ten-zumi, 点炭, offer-charcoal, is separate from the other charcoal pieces, and may represent the ryūsha, 竜車, dragon-cart.

The two pieces of neriko may represent the hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel. The hōju holds Buddhist scripture.

Hana-ire, 花入, flower-receptacle; Kara-kane, 唐銅, Tang-copper, bronze, Kyō-zutsu, 経筒,Sutra-cylinder, with dome-lid and hō-ju tsumami, 宝珠摘, treasure-jewel pinch, by Kana-mori Shō-ei,金森紹栄, Gold-forest Help-flourish, Taka-oka Shi, 高岡市, High-hill City. Usu-ita, 薄板, thin-board; ya-hazu ita, 矢筈板, arrow-nock board; black-lacquered wood with notched edge; 14 x 9 sun kane-jaku.

The kyō-zutsu takes the place of parts of the spire: ku-rin, 九輪, nine-rings, sui-en, 水煙, water-smoke, and the ryū-sha, 竜車, dragon-car. This makes a total of eleven parts – jū-ichi, 十一, ten-one. In Buddhism, the number eleven evokes the eleven-heads of the Jū-ichi-men Kan-non, 十一観音, Ten-one-face See-sound.

The garden of a cha-shitsu, 茶室, tea-room, is called a ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground. Ideally, the garden is divided into the soto ro-ji, 外露地, outer dew-ground, and uchi ro-ji, 内露地, inner dew-ground, that is the location of the tea room. The essential feature of the inner roji is the tsukubai, 蹲, crouch-down, which centers on a stone basin, chō-zu bachi, 手水鉢, hand-water bowl.

The Kanji ro, 露, means dew, tsuyu, as well as in the open air, or revealed, which in Buddhism implies ‘enlightenment’, satori, 悟. As its name indicates, the roji garden is open to the sky, whereas in Buddhism, the chōzu bachi is usually roofed over. In Shintō, the stone basin of purifying water is quite often open to the sky, as well as located in a housing. Shintō shrines are frequently located near a mountain stream, the water flowing into a stone basin.

A popular feature of chōzu bachi is a bamboo spigot that continuously directs water from its source to the basin. This is not a part of the tsukubai of the Tea roji. The water in the chōzu bachi is replenished by the host, just prior to its being used to purify the hands and mouth before entering the Tea room

Another essential aspect of the tsukubai area is a lantern, preferably made of stone – ishi dō-rō, 石灯籠, stone lamp-basket. The lantern is often modeled after the hō-tō, 宝塔, treasure-tower, which holds the relics of the Buddha. The stone lantern beckons the worshipper, and establishes the north direction. The hōtō is composed five parts inspired by the go-rin-tō, 五輪塔, five-ring tower, symbolic of the five principles. The uppermost element of the tower is identified with the hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel, which may evoke the roban and hōju finial of the Buddhist sutra treasury, kyō-zō, 経蔵.

Figure of Bi-sha-mon-ten, 毘沙門天, Assist-sand-gate-heaven (Deva), gilt wood. Copy of Tang Chinese figure that once was located in the main gate of Hei-an-kyō, 平安京, Level-peace-capital.

Bi-sha-mon-ten, 毘沙門天, Assist-sand-gate-heaven (Deva) is the Buddhist guardian of the north, and who leads the Shi-ten-nō, 四天王, Four-heaven-kings, Buddhist guardians of the four directions. Bishamonten plays dual roles, including Ta-mon-ten, 多聞天, Multi-listen-heaven, who also guards the north. Bishamonten holds aloft on his left hand, the hō-tō, 宝塔, treasure-tower. Note the pagoda has the sōrin on its roof.

Bishamonten can be seen as the guide for both the host and the guests during the presentation of Tea. Just as the pagoda is the illuminating device held in the left hand of the deity, the tea container is held in the left hand in order to prepare a bowl of Tea, uniting all participants in harmony.

For further study, see also: Ro: November Opening and Tea Utensils: Roots in Heaven