Setsubun: The Fortunes of Spring

Uchiwa, 団扇, round-fan, paper on split bamboo with calligraphy, Shichi-ten ha-kki, 七転八起, seven-fall down eight-get up, and images of roly-poly dolls of Daruma enrobed in white with the Kanji fuku, 福, fortune, and O-ta-fuku, お多福, Hon.-much-fortune, as Hime Daruma, 姫だるま, Princess Daruma, dressed in red with the Kanji for kotobuki, 寿, longevity.

Daruma, said to be the founder of Chan/Zen Buddhism, is depicted with a te-nugi, 手拭い, hand-wipe, as a hachi-maki, 鉢巻, bowl-wrap, around his head, indicating his effort and spirit needed to achieve a goal.

Otafuku is an image that is related to providing joy and good fortune. Depicting these two deities together combines aspects of Buddhism and Shintō together as Otafuku is often recognized as a different depiction of the Shintō goddess, Ame no Uzume no Mikoto.

In Japan there is often an overlap between Shintō and Buddhist traditions, this is referred to as Shin-butsu-shū-gō, 神仏習合, god-buddha learn-join. In Japan, unlike in many western traditions, the ways of Buddhist and Shintō ideas and ideals are incorporated into daily life, and act as a type of ethical or moral code. While there is also distinct separation of the religious aspects of Buddhism and Shintōism, Shinbutsu shūgō is present in many aspects of Japanese culture, particularly in matsu-ri, 祭, celebrations. The uchiwa depicted above could easily be used during a Daru-ma Matsuri, 達磨祭, Attain-polish Celebration, of which there are two dates that are celebrated in different forms, there is a Daruma Matsuri held around the time of Bodhidarma’s death, and another Daruma Matsuri is regionally held around the time of the new year. This uchiwa is most likely to be used as an emblem in the new year celebrations.

However, here is also the possibility that the uchiwa could be used during the celebration of Setsu-bun, 節分, Season-divide. Setsubun is widely considered as the day before the first official day of spring and, Otafuku is almost invariably represented at this time. The multifunctional aspects of depicting deities from two different traditions in one object serves multifunctional representations, which can be as unique as the person who possesses such an object.

On the uchiwa is written ‘Shi-chi-ten ha-kki’, ‘Fall down seven get up eight’, which can also be written as ‘nana korobi ya oki’, 七転び八起’. Either interpretation can be understood to mean ‘fall down seven times, get up eight’.

Oki-agari-ko-bō-shi, 起き上がり小法師, Get-up small-law-master, monk; ceramic figures of Daruma and Hime Daruma who is a manifestation of Otafuku. Both figures are shaped like gourds, hisago, 瓢, which is also read fukube, including the word fuku, suggesting good fortune.

Daruma, as a representation of Buddhist ideals, embodies the attributes of perseverance and tenacity, whereas Otafuku, as a representation of Shintō ideals, is a representation of joy and mirth, particularly when Otafuku is considered as a manifestation of Ame no Uzume no Mikoto, who is widely known in the tales contained in both the Kojiki and the Nihon Shōki. According to ancient lore, Ame no Uzume made a display of such joy that the gods laughed hard enough to cause Ameterausu, the Sun Goddess, to emerge from her cave. * Note for further study of this story, see links below.

The depiction of the Buddhist deity Daruma, who represents the masculine Yō, 陽, Penetrative, principle, coupled with Otafuku who represents the feminine In, 陰, Receptive, principle is a reminder that balance between perseverance and joy is necessary for humans to lead a life of accomplished presence, a state of equilibrium that is full of life. Not too harsh, nor too yielding. This principle can be referred to as Nagomi, 和み, harmony-body, which also presents in human expression as tranquility or peaceful calm as one moves through the world – both accomplishing goals, and enjoying the journey, simultaneously.

Sculptural image of Okame, おかめ, Hon. turtle, at Sen-bon Shaka-dō, 千本釈迦堂, Thousand-origins Explain-(sound)-hall, also referred to by its temple name Dai-hō-on-ji, 大報恩寺, Big-reward-grace-temple. Senbon Shakadō is a designated national treasure and is one of the oldest wooden structures in Kyoto.

View of the main hall Sen-bon Shaka-dō, 千本釈迦堂, Thousand-origins Explain-‘ka’-hall, Kyōto.

Okame was the wife of the master carpenter of the temple, who was faced with an issue in the construction around 1227. He had cut the central pillar too short to maintain the structure’s integrity, and asked his wife for help, to which Okame gave her advice. At that time it was considered a great disgrace for a man to receive and follow the advice of a woman. Okame sacrificed herself twice for her husband’s honor, first in offering the idea to reorient the original structural plan of the temple to her husband, and again when she is alleged to have taken her own life prior to the opening of the temple, so that her husband would not face humiliation. Both of her deeds have been framed as acts of compassion.

To honor her, it is said that the carpenter carved a mask of her face and hung it on the central pillar so that Okame could see the finished temple. As a result the temple features many masks in her likeness, which is also that of Otafuku.

The monument depicts Okame as a manifestation of O-kame-ta-fuku, 阿亀多福, Praise-turtle-much-fortune, which is written on the memorial plaque beneath the statue. The statute is flanked by a set of shi-de ,四手, four-hand, made of wood reflecting a distinct aspect of Shintō tradition. Many people visit the statue to pray for good marriages and easeful childbirth.

The image shows Okame holding an architectural form supporting a hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel, bearing the Buddhist Sanskrit seed character, hrīh, ह्रीः, Japanese, hīuri. This seed sound is often associated with Amida, and can also be attributed to Kannon. The Sanskrit sound, as it relates to Buddhist principles, represents the attributes of self respect or conscientiousness, as well as honor. In Vajrayana Buddhist practices, it relates to the heart center.

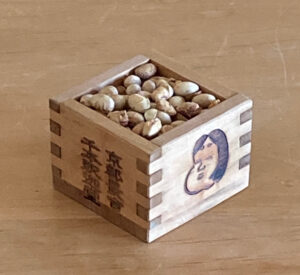

Fuku-masu, 福枡, fortune-box measure, square box made of sugi, 杉, cedar, with branded design of O-kame, お亀, Hon.-turtle, and the name of the temple, Sen-bon Shaka-dō, 千本釈迦堂, Thousand-origins Explain-‘ka’-hall, Kyōto. The masu is filled with parched soy beans.

The seasonal festival associated with Otafuku is Setsu-bun, 節分, Season-divide. This is a seasonal celebration that is observed in both Buddhist and Shintō traditions. Setsubun occurs on the first day before spring according to the 72 seasonal divisions of the year. As part of the celebration, at both Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines, as well as in individual households, images of Otafuku can be seen and people participate in the purificatory and celebratory throwing of beans out of entranceways called mame-maki, 豆撒き, bean-scattering while exclaiming ‘oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi’, 鬼は外 福は内, demon out fortune in. Celebrating Setsubun is a way to both clear out the old and welcome in the fortunes of Spring. Sō-tan, 宗旦, Sect-dawn, Grandson of Rikyū, scattered beans from the nijiri-guchi, 躙口, edge forward-opening, to his Yū-in, 又隠, Again-retire, tea hut, for placing the stepping-stones of the ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground.

In Buddhist thought, the oni/demons are representations of the human aspects of aversion, ignorance, and desire, which manifest in the emotions of anger, indifference, and greed. At many temples the phrase ‘Demons out, fortune in’ is replaced with ‘Long life, fortune in’, as it is thought that demons are unable to exist in the presence of the deities of Buddha and Kannon.

In Shintō, the oni/demons symbolize misfortune, disease, and negative energy. In both systems there is a conjunction of purification and celebration.

The oni may represent the harshness of winter, and Otafuku the abundance of spring.

Cha-wan, 茶碗, tea-bowl, conical ceramic bowl in the style of ten-moku, 天目, heaven-eye, with black glaze and calligraphy in gold written from left to right, ki sa ko, 喫茶去, drink tea depart(!), with illegible signature. The bowl may have been from a number of tea bowls at a temple.

Some scholars suggest that the Kanji, 去, is used like an exclamation point, that is intended as advice for one to simply ‘drink tea !’, and not ‘to leave’.

In the practice of Chanoyu, Setsubun is also an important day as it is the eve of Ri-sshun, 立春, Start-spring, and an important marker for hachi-jū-hachi-ya, 八十八夜, eighty-eighty nights. Tea people often celebrate the marker Setsubun and Risshun after Risshun, because 88 nights later marks the start of the first tea harvesting tea. The date varies from May 1 to May 2. It is a great moment in the life of Chanoyu. It is an impossibility to pick all the tea on one day, the period of cha-tsumi, 茶摘, tea-pick, begins ten days before, and ten days after hachi-jū-hachi-ya. This period of twenty-one days is the source of the name of mukashi, 昔, past, for certain teas. The Kanji for mukashi, 昔, is composed of the Kanji for twenty, 廿, which is two tens, 十十, one, 一, and sun or day, 日, which equates to the number of days for picking tea. The first tea ‘name’ was ‘Hatsu-mukashi’, 初昔, First-past, and this actually means the early part of the twenty-one days, and it is when the highest quality tea leaves are available.

For some tea people Setsbun is a celebratory anticipation and the start to the countdown of days when the work of harvesting fresh tea leaves will begin. And like all days, Setsubun is a great day to sit and enjoy a bowl of tea, and intentionally celebrate the fortunes of Spring.

For further study, see also: Setsubun and Otafuku Collection

To see and hear Allan Sensei share the story of Ame no Uzume no Mikoto and Amaterasu, visit the Tea Talk: Setsubun Lecture