Jizō Bon

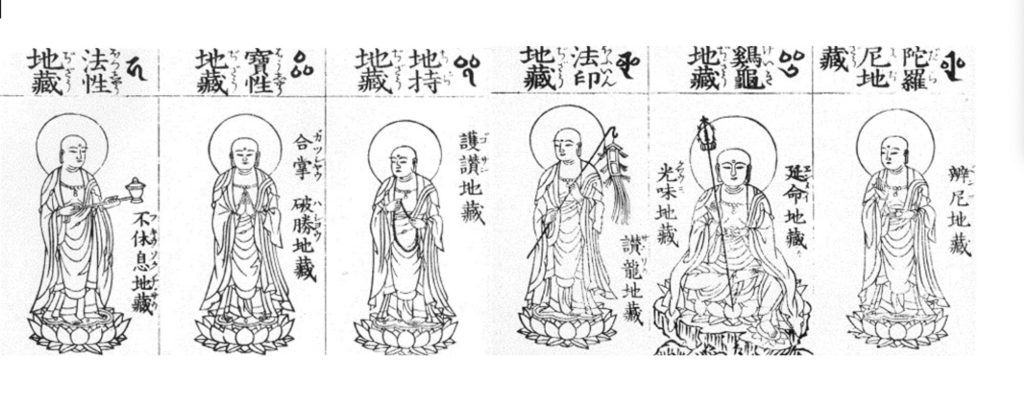

The Buddhist deity, Ji-zō Bo-satsu, 地蔵菩薩, Earth-keep Grass-buddha, is Japanese for the Indian Buddhist deity, Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva. Jizō is the guardian of the world until the coming of Maitreya, (Mi-roku Bo-satsu, 弥勒菩薩, Increase-rein Grass-buddha). Usually depicted as a monk with a halo around his shaved head, he carries a shaku-jō, 錫杖, tin-staff, to force open the gates of hell and a wish-fulfilling hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel, to light up the darkness. There are many variations in form and size of the shakujō, including a small hand-held implement used in prayer.

The origins of Ksitigarbha are vague, and may be a Chinese creation. It was written, that toward the end of his life, the Buddha mourned the death of his mother, and he told the story of a young virtuous Brahman maiden who mourned the death of her mother, and saw the suffering of souls in hell.

The images of Jizō make him appear like a child, innocent, and almost without specific gender. He is the guardian of children, and in a way is like the child that a parent has lost. Jizō becomes like that child who comforts the parent, having been shown the way to paradise and rest through the compassion of Jizō. This parent-child relationship is the foundation of Jizō Bon. Have no fear.

Images of Jizō are often adorned with red cloth hats and bibs, which are closely identified with a newborn who is called an aka-chan, 赤ちゃん, red-‘baby’.

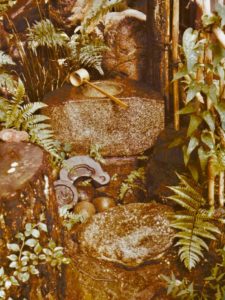

There are uncountable images of Jizō throughout Japan that are made of stone, ishi Jizō, 石地蔵, stone Jizō. Stones are regarded as eternal, although time has proven that idea is wrong. In Buddhism, everything in perishable. Only spirit is eternal.

Ji-zō Bon, 地蔵盆, Earth-keep Tray, is a special Buddhist event honoring Ji-zō Bo-satsu, 地蔵菩薩, Earth-keep Grass-buddha, which is separate from the traditional O-bon, お盆, Hon.-tray. Obon is a lunar event which is observed on the fifteenth day of the seventh lunar month. However, in some places in Japan, Obon is popularly observed on July 15. It is also observed one month later, on August 15, and in some areas, Obon is observed on the day of the seventh full moon, which occurs in August.

August 21 – Kyū Ji-zō Bon, 旧地蔵盆, Old Earth-keep Tray, this is according to the old lunar calendar the 24th day of 7th month, on which solemn rites held in honor of Jizō Bosatsu.

August 24 – Ji-zō Bon, 地蔵盆, Earth-keep Tray, occurs in Kyōto, when Buddhist rites held in honor of Jizō, especially for children.

On the 28th day of the 7th moon, is the solemn rites dedicated to Dai-nichi Bon, 大日盆, Great-sun Tray. The 28th day of each month is the En-nichi, 縁日, Affinity-day, of Dainichi.

This Buddhist festival of Obon has been observed for more than five hundred years. It originated from the story of Maudgalyayana (Moku-ren, 目連, Eye-lead), who was a close disciple of Buddha. He used his powers to see the spirit of his deceased mother, who had fallen into the Realm of Hungry Ghosts and was suffering. The important aspect is the realm of the Hungry Ghosts, Ga-ki-dō, 餓鬼道, Hungry-demon-way, the fifth lowest level of the Roku-dō, 六道, Six-ways, the six realms of human existence.

The six realms of existence are Ji-goku-dō, 地獄道, Earth-prison-way, Ga-ki-dō, 餓鬼道, Hungry-demon-way, Chiku-jō-dō, 畜生道, Animal-life-way, Shu-ra-dō (Asura), 修羅道, Discipline-spread-way, Jin-dō, 人道, Person-way, Ten-dō, 天道, Heaven-way.

Jizō’s powerful vow is to be present for all suffering beings in all six realms. Jizō is everywhere, but he is particularly known and appreciated for aiding hungry ghosts and beings in hell. In the realm of the Hungry Ghosts, there are thirty-six kinds of ga-ki, 餓鬼, hungry-ghost, who, in life, behaved in unacceptable ways, and will agonize with insatiable hunger, until they are saved by Jizō and other Buddhist deities.

The real purpose of the Tearoom is to offer tea and food and drink. It is a kind of dining room in the western sense. Jizō is the host, servant, and attendant to the guests, who are spirits in transition to a higher realm. Jizō is feeding them food and drink in a Buddhist setting of the Tearoom.

The gaki are represented as supporting stones for the images of the Shi-ten-nō, 四天王, Four-heaven-kings. These gaki stones are present, metaphorically in the ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground, garden of the Tearoom. Google translates the word ga-ki, 餓鬼, hungry-ghost, as ‘brat’.

Jizō is often depicted holding a shaku-jo, 錫杖, tin-staff, in his right hand. The shakujō is composed of a wooden staff with a ‘finial’ of metal. The ‘finial’ is often flame-shaped ring with adornments including the Go-rin-tō, 五輪塔, Five-ring-tower, which is emblematic of the immortal soul. There are six loosely attached metal rings that, when the staff strikes the ground, the rings make noise. The shakujō is used to make a jingling sound to frighten away insects or other animals so that they would not be injured. It has been used as a weapon.

The shakujō is believed to have been created by Kassapa, a follower of the Buddha. The rings are divided with three on both sides of the main ring. Each one of the six rings is identified with one of the Roku–dō, 六道, Six-ways, where one of the six manifestations of Jizō is a guardian.

A shakujō is carried by Jizō Bosatsu, Sen-jū Kan-non Bo-satsu, 千手観音菩薩, Thousand-hand See-hear Grass-buddha, and Jū-ichi-men Kan-non Bo-satsu, 十一面観音, Ten-one-face See-hear Grass-buddha. The long wooden staff is used by Jizō to measure the depth of the San-zu-no-gawa, 三途川, Three-crossing-river, that souls must cross to enter paradise.

The six rings, roku-kan, mutsu-kan, 六鐶, six-(metal) rings, refer to the six realms of existence that are protected by Jizō. These six realms are called the Roku-dō, 六道, Six-ways, which refers to hell at the bottom and heaven on top. They also are identified with the six perfections that lead to nirvana: generosity, morality, patience, vigor, concentration, and wisdom. The rings are divided so that there are with three rings on either side of the central element. Is this arrangement simply for balance and symmetry or is there some symbolic significance?

The six realms from the bottom are called the Three Evil Paths, which are hell, hungry ghosts, and animals. Above these are the states of demi-gods, humans, and gods. The six rings may also be identified with the six-syllable mantra of Kannon Bosatsu: om ma-ni pad-me hum, om jewel lotus hum. Jizō is devoted to Kannon, and is often depicted with Kannon and A-mi-da, 阿弥陀, Praise-increase-steep, the Buddha of Compassion, who dwells in the western paradise of Jō-do, 浄土, Pure-land.

Sen no Rikyū had a walking stick called a ro-ji zue, 路地杖, dew-ground staff. It was made of bamboo that had nana fushi, 七節, seven nodes, which created six chambers, roku kan, 六間. The length of the bamboo is san shaku, 三尺, yon sun, 四寸, go bu, 五分, [approximately 40 inches].

When in the roji garden, the guest must carry the sensu / folding fan, in the right hand. The standard length of a man’s sensu is roku sun, 六寸, (approximately 7 1/8 inches). Perhaps there is a correlation between the six rings of the shakujō and the six chambers of the bamboo staff and the six sun of the fan. If there are such connections, it would be that the guest holding the fan is emulating Rikyū’s bamboo staff and Jizō’s shaku–jō. It would be that Jizō, guardian of travelers, is guiding the guest through the roji to the Tea room, a realm of Buddhist haven.

The number six may be identified with the Go-rin, 五輪, Five-rings, symbolic of the five principles: Chi, 地, Earth; Sui, 水, Water; Ka, 火, Fire; Fū, 風, Wind; Kū, 輪, Void. Collectively they may be identified as a sixth principle, Shiki, 識, Consciousness. Thus, a single object that may manifest the five principles becomes a symbol of consciousness.

Of the five principles, Wind is difficult to manifest in the procedures of Chanoyu. However, the function of a sensu is to move air and create wind. Curiously, in Chanoyu, the sensu should never be used to fan oneself.

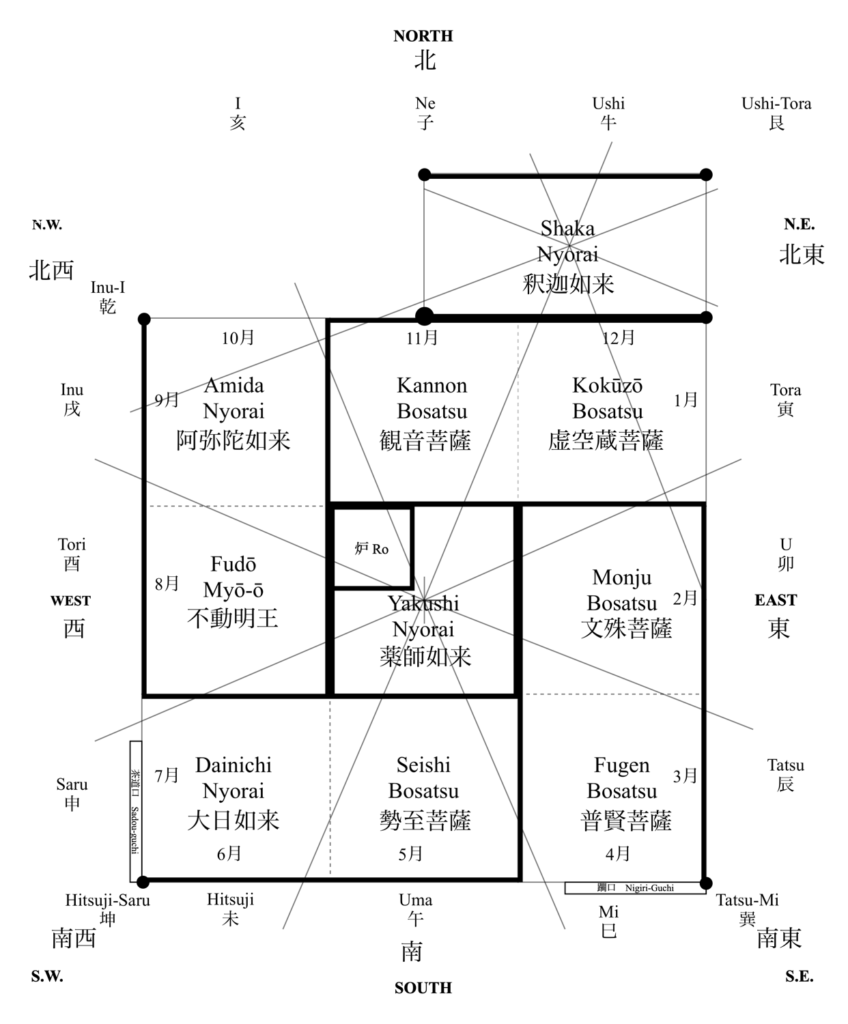

Diagram of the yo-jō-han, 四畳半, four-mat-half: showing directions, lunar months, [1月], the Jū-ni-shi, 十二支, Ten-two-branch, animal signs; the locations of Buddhist deities, Nyo-rai, 如来, Like-become, Bosatsu, 菩薩, Grass-buddha, and Myō-ō, 明王, Bright-king. Lunar Tanabata, 七夕, Seven-night, occurs on the 7th night of the 7th moon, and Lunar O-bon, お盆, Hon.-tray, occurs on the 15th day of the 7th moon. Lunar Ji-zō Bon, 地蔵盆, Earth-keep Tray, occurs on the 21st day of the 7th moon, and Kyōto Ji-zō Bon occurs on the 24th day of the 7th moon. Each of these events can be found on the diagram in the location of the Cha-dō-guchi [Sadōguchi], 茶道口, Tea-way-opening, the entrance used by the tei-shu, 亭主, house-master, acting on behalf of Dai-nichi Nyo-rai, 大日如来, Great-sun Like-become, and Fudō Myō-ō, 不動明王, No-move Bright(Wisdom)-king.

On the 28th day of the 7th moon, is the solemn rites dedicated to Dai-nichi Bon, 大日盆, Great-sun Tray. The 28th day of each month is the En-nichi, 縁日, Affinity-day, of Dainichi. As Fudō Myō-ō, 不動明王, No-move Bright-king, is the wrathful manifestation of Dainichi, both of these deities may be metaphorically located at the Chadō-guchi, and symbolically identified with the teishu.

Ji-zō Bo-satsu, 地蔵菩薩, Earth-keep Grass-buddha, guards the world until the arrival of Mi-roku Bo-satsu, 弥勒菩薩, Increase-rein Grass-buddha. His Buddhist counterpart is Ko-kū-zō Bo-satsu, 虚空蔵菩薩, Empty-void-keep Grass-buddha. Jizō is often likened to Kan-non -Bosatsu, 観音菩薩, See-hear Grass-buddha, who is the Buddhist goddess of mercy and compassion. Jizō and Kannon are both saviors of the less fortunate, children, and those who are lost.

Jizō has six manifestations, and the number six is emblematic of one surrounded by five. Kannon has thirty-three manifestations, which is emblematic of the center surrounded by thirty-two radiating outward in every directions. Sen-ju Kan-non Bo-satsu, 千手観音菩薩, Thousand hand See-sound Grass-buddha, holds in her many hands various implements, including the shakujō. Kokūzō is one of the eight Buddhist guardians of the cha-shitsu, 茶室, tea-room, as he is the protector of the Asian zodiac signs of Ushi, 丑, Ox, and Tora, 寅, Tiger, and collectively as Ushi-Tora, Kon, 艮, stopping, northeast, etc.

Jizō has no specific role in the iconography of the chashitsu, however, his spiritual presence permeates the earthly world, and, especially, the ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground, the garden of the Tearoom. Ideally, the roji has a stream of water, and living things such a moss, plants, trees. There are two roji, uchi-roji and soto-roji.

The uchi-ro-ji, 内露地, inner-dew-ground, which contains the cha-shitsu, 茶室, tea-room and the tsukubai, 蹲, crouch, also written 蹲踞, crouch-hover, is a sort of spiritual realm. The uchi-roji has a basin full of purifying water. Images of Jizō are often located near waterfalls or fountains, and there are basins specifically created for Jizō, where his figure has water poured over or splashed upon it. The soto-ro-ji, 外露地, outer-dew-ground, which has a waiting bench, koshi-kake machi-ai, 腰掛待合, bottom-hang wait-gather, and is a sort of physical realm.

The uchi-roji and soto-roji are separated and joined by a chū-mon, 中門, middle-gate, which is borrowed directly from the often monumental gateway to a Buddhist temple. The chūmon may be as simple as a swinging gate flanked by two posts, to an elaborate, roofed structure. Temple gates often have guardian deities or animals.

In the Tearoom, the most important object for tea is the cha-wan, 茶碗, tea-bowl.

Perhaps because of its close connection with Buddhism, the flower of the lotus is not regarded as appropriate for Chanoyu. According to Rikyū’s Seven Rules of Chabana, neither is the distant cousin, sui-ren, 睡蓮, sleep-lotus, the waterlily, and the kō-hone, 河骨, river-bone, a variety of small yellow flower water plant, that is unapproved because of its disturbing name.

In the furo summer season, one of the most preferred cha-bana, 茶花, tea-flower, is the muku-ge, 木槿, tree-rose of Sharon. Somewhat strange, is that the Kanji for lotus, 蓮, can be read hachi-su, bee-nest, and that refers to the rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus). In an elliptical way, the ‘lotus’ is presented as cha-bana, 茶花, tea-flower.

The close association between the hibashi, 火箸, fire-rods, and the kan, 鐶, metal rings, used to move the kama, 釜, kettle, may suggest identification with Jizō’s shaku-jō, 錫杖, tin-staff. The hibashi are used to move burning charcoal, which could suggest Jizō’s using his shakujō to thrust open the gates of hell. The kettle rings resemble the rings hanging from Jizō’s shakujō. The shakujō is also made with a short handle to use during prayers.

One of the six manifestations of Jizō holds a banner called a dō-ban, 幢幡, banner-flag. The kake-mono, 掛物, hang-thing, is an essential aspect of a Tea gathering, and it has the spiritual nature that is inherent in the Buddhist dōban. The dōban is a hanging banner used as ornament in Buddhist temples. The stick that supports the banner, is like the stick that may be used to hang a scroll in the tokonoma. Such banners are part of Buddhism and Taoism, and bear various texts including invocations.

The banner is made of cloth, and there are several cloths of fine and symbolic quality used in the Tearoom, such as the fukusa, 帛紗, cloth [silk]-gauze, ko-buku-sa, 古帛紗, old-cloth-gauze. The texts inscribed on the banners are most often composed of a vertical line of six characters, although there are longer texts. The banner or pendant is supported on a free-standing pole. Lotus motifs are often included in the ornamentation.

These sweets were first made at Shimo Gamo Jinja, 下鴨神社, Lower Duck God-shrine, where people rinsed their hands in the river water, before entering the shrine. These were originally called Kamo Mitarashi dango, after the Kamo River in Kyōto. These timeless ancient sweets may resemble somewhat the string of beads held by Jizō.

Jizō also holds a ju-zu, 数珠, multiple-jewels, which is a continuous string of beads made of a variety of materials and different numbers of beads. The essential purpose of the juzu is to keep track of the number of prayers and incantations. The manner of manipulating the beads permits the brain to focus on chanting or prayer rather than keeping track of the repetitions. Each string or strings has a major bead and one or two tassels, which aid in keeping count.

The juzu may have had origins in Brahman culture for more than 3500 years. Strings of beads were introduced to Japan along with Buddhism in the sixth century. Many Buddhist followers wear a string of beads on their wrist, or carry on their person. There are various kinds of juzu, and they often have specific associations with various Buddhist sects. The beads vary in number, with 108 beads as a kind of standard, which bears wide symbolic significance in Buddhism. The beads are made of a multitude of materials, including various woods and stones and fruit stones and seeds. A bead may be carved or decorated with geometric or foliate designs, written characters, deities, etc.

Left: sculptural image of a hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel, held on the left hand of a figure of Jizō. Center: ceramic kō-gō, 香合, incense-gather, in the form of a hōju, ki-Se-to, 黄瀬戸, yellow Rapids-gate. Right: ho-ya gō-ro, 火舎香炉, fire-house incense hearth, incense burner borrowed from the Buddhist altar, used as a futa-oki, 蓋置, lid-place. The incense burner form is based on the hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel.

There are no living things in the cha-shitsu, 茶室, tea-room, other than people. The flower is cut, and therefore not actually living. The world is alive with living things. Ideally, there are no flowering plants or flowering trees growing in the uchi ro-ji, although there might be flowering trees, such as the ume, 梅, flowering prunus, in the soto ro-ji. Rikyū believed that a pine tree should be growing near the Tea hut.

The principle role of Jizō is to protect souls that are reborn in the netherworld to help them cross the San-zu no Kawa, 三途の川, Three-crossing ’s River, which is somewhat like the Buddhist version of the river Styx. The departed souls of children must stack up stones, which are knocked over by demons.

Sai no Ka-wara, 賽の河原, Contend ’s River-field, children’s Buddhist ‘limbo’. The children must pile up stones for their own eternal monument, which are knocked over by the minions of Datsueba. It is a custom around the world for people to pile up stones as a kind of monument. Seki-tō, 石塔, stone-tower, creating one’s own Go-rin-tō, 五輪塔, Five-ring-tower, a monument to one’s immortality of soul.

Datsu-e-ba, 奪衣婆, Rob-clothes-old woman, is said to meet wandering souls fourteen days after their death, and she takes their clothes. The deity of the Jū-san-butsu, 十三仏, Ten-three-buddhas, who presides over the soul during the second seven days is Sha-ka Nyo-rai, 釈迦如来, Explain-(sound) Like-become, the historical Buddha. Datsueba may be likened to the midwife to eternity.

Jizō hides the children within his great robe, and comforts them. With his shakujō he tests the depth of the river so that it is safe to cross. The greater the sins, the greater the depth. However, children are without sin. Perhaps Datsueba, by taking their clothing, in a way returns the children to the way in which they were born. Clothing may be a sign of having the knowledge of being naked, just as Adam and Eve covered their nakedness in shame.

It is said that the origin of the name of the Sanzu River is that in the early days there were three methods of crossing the river. According to the Jizō Sutra, the three ways are: ichi san-sui-se, 一山水瀨, one mountain-water-rapids; ni kō-shin-en, 二江深淵, two bay-deep-abyss; san ari-hashi-watari, 有橋渡, three have-bridge-cross. It was said that good people would cross a bridge of Kin–gin Shi-ppō, 金銀七宝橋, Gold-silver seven-treasures.

The sensu for Chanoyu has thirteen hone, 骨, bone, ribs, or more specifically, ko-bone, 子骨, small bones, ribs, and two cover pieces. The thirteen hone may be identified with the thirteen Buddhist guardians: Jū-san-Butsu, 十三仏, Ten-three-Buddhas. Jizō is one of the Jū-san-butsu, 十三仏, Ten-three-buddhas, who preside over the periods of time after one’s death. Jizō presides over the go shichi-nichi, 五七日, five seven-days, or san-jū-go-nichi, 三十五日, three-ten-five-days.