Chanoyu and August in Japan

August, Hachi-gatsu, 八月, Eight-month; the old name for the Eighth month is Ha-zuki, 葉月, Leaf-month.

August in Japan is filled with festivals and religious activities. Many events that were originally held on dates according to the old lunar calendar, kyū-reki, 旧暦, old-calendar, are held on the same dates, but in the solar calendar. The most important event of the ‘summer’ is O-bon, お盆, Hon.-tray, which is traditionally held on the fifteen day of the seventh month in accord with the full moon. The seventh lunar month is also called Ki-zuki, 鬼月, Demon-moon, which in China is translated into English as ‘Ghost Month’.

In modern times, Obon is observed by millions of Japanese on July 15. Traditionalists, however, observe Obon in August with the full moon, and in the year 2022, Kyū-bon, 旧盆, Old-tray, is observed on August 12. Leading up to Obon, is another very much celebrated event, Tana-bata, 七夕, Seven-night, when poems and prayers are offered to two stars that are seen as lovers with major challenges. Tanabata is a lunar event, but is more popularly observed on July 7th, whereas, the traditional seventh night of the seventh moon is observed in 2022 on August 4, and with a half-moon. Tanabata is preparation for Obon that occurs seven days later.

A tanzaku is written during the observance of the festival of Tana-bata, 七夕, Seven-night, which occurs on the seventh night of the seventh month. An event that began in China long ago, which focuses attention on the stars of the Summer Triangle of Altair, Vega, and Deneb.

Deneb is in the tail of Cygnus, Altair is in Aquila, and Vega is in Lyra.

When these stars are connected with lines, they form the ‘Summer Triangle’, in Japanese, Natsu no Dai-san-kaku, 夏の大三角, Summer’s Great-three-corner.

Although this Star Festival was originally a lunar calendar event, in Japan, it is celebrated on July 7, and August 7, and on the seventh night of the lunar seventh month, which varies from year to year.

The stars of Tanabata – Altair is identified as Hiko-boshi, 彦星, Boy-star, and Ken-gyū,牽牛, Lead-ox, and Vega as Ori-hime, 織姫, Weave-princess. Their story is of a love that was so intense that they shirked their duties, so that the king, her father, forbad them to meet, and separated by the Milky Way, the River of Heaven. The lovers were so upset that the king allowed them to meet once a year, the seventh night of the seventh month. A bridge of magpies allowed them to cross the Milky Way and meet. The star Deneb is various identified, and has been identified as the bridge itself, Ama-no-hashi, 天橋, Heaven’s-bridge.

The word Tanabata, which has no real relationship to the Kanji 七夕, is derived from tana-bata tsu-me, 棚機津女, shelf-loom port-woman, which is one of the names of the weaver princess. The word ‘port’ is the location of the weaver princess by the side of the River of Heaven.

To honor the stars, the Japanese people place in front of their door a stalk of sasa, 笹, bamboo grass, and decorate it with tanzaku and other ornaments. Poems, requests, and prayers are written on rather thin paper strips and tied with strings on the branches. At the end of the observances, the bamboo and its adornments are placed in a river to eventually enter the Milky Way.

Traditionally, they wrote on kaji no ha, 梶の葉, paper mulberry ’s leaf. The inner bark of the paper mulberry tree was and is used to make paper in Japan. The leaves of the tree have five lobes, three of which seem suited to the classic poetry of hai-ku, 俳句, actor-phrase, which consists of 5, 7, and 5 syllables.

There is a much deeper purpose of the display of the bamboo stalk in front of the home. Tanabata on the seventh night when there is a half-moon. In seven days is the full moon, and it is on the full seventh moon, that the spirits of the dead return to their ancestral homes. This is occasion is O-bon, お盆, Hon.-tray, which is when millions of Japanese people return to their homes to honor their departed ancestors. Only the New Year is a greater holiday.

Tanabata begins the preparations for Obon, when the house is cleaned meticulously, and elaborate settings of highly symbolic objects are created. The cleaning is more of a purification which is called o-harai, お祓, hon.-exorcize. The means of much of the cleaning is dusting with a long stalk of leafy sasa bamboo grass, which is used like a flail. In Shintō rites of purification, cut strips of hemp paper are attached to the branch to add a touch of sanctity, as hemp paper and fabric are sacred to Shintō. It is out of this ritual that the bamboo stalk with its strips of paper is displayed in front of the home to show that preparations are being made in anticipation of Obon. In another similar act, seven days for before the New Year, a sprig of sasa bamboo grass is closed in the front door or gate of a house to show that the inhabitant are cleaning if preparation for O-shō-gatsu, お正月, Hon.-correct-month.

In the Nara period, Tanabata, introduced from China, was held in the Imperial Palace. Offerings included momo, 桃, peach, nashi, 梨, pear, na-su, 茄子, eggplant, uri, 瓜, melon, dai-zu, large-bean (soybean), hi-dai, 干鯛, dried abalone, usu-awabi, 薄鮑, abalone, etc. These were offered in the eastern garden of Sei-ryō-den, 清涼殿, Pure-refreshing-mansion, and offered to the two stars, Ken–gyū, 牽牛, Lead-ox, and Shoku-jo, 織女, Weave-woman, where they were enshrined.

August 4 in 2022 is Kyū Tana-bata, 旧七夕, Old Seven-night; a lunar event more popularly observed on July 7. The moon of the seventh night is han-getsu, 半月, half-moon. Elaborate displays of bamboo poles, take-zao, 竹竿, bamboo-stalk, decorated with tanzaku with prayers and poems dedicated to the stars of Altair and Vega. Tanabata is the traditional beginnings of preparations for Obon, when departed spirits return home, and are honored on the full moon.

The kind of bamboo that is used is slender and retains its leaves. The most familiar bamboo is sasa, 笹, which is a kind of grassy bamboo that retains some of it sheathes. Bamboo attains its greatest height in early autumn, which may be the reason why bamboo is used for Tanabata festivities.

From the top of the illustration is the Weaver Princess and her loom, and three birds. Across a stream is the Oxherd and his ox. Below some clouds is a woman playing a horizontal harp, surrounded by other musical instruments, and behind her is a table with offerings, and two bamboo stalks tied together with a ribbon. Tana-bata Tsu-me, 棚機津女, Shelf-loom Port-woman. The woman in the illustration plays the koto that somewhat resembles the weaver’s loom of the princess.

The weaver lady is Ori-hime, 織姫, Weave-princess, and the Oxherd is Ken-gyū, 牽牛, Lead-ox. He is the personification of the star Altair in the constellation Aquila, and she is the personification of the star Vega in the constellation Lyra. They are on opposite sides of the Ama-no-kawa, 天の川, Heaven’s-river, the Milky Way. Orihime is a weaver, just as Amaterasu is a weaver, and a weaver of asa, 麻, hemp.

The love between the princess and the herder was such that they neglected their duties, so that her father, the king, forbade them to ever meet again, and put them on opposite sides of the river of heaven, the Milky Way. After much lamentation, the king allowed them to meet once a year on the seventh night of the seventh moon. They could cross the river by means of a bridge made of birds.

The bird, or birds, was the kasasagi, 鵲, magpie, and the bridge is called shaku-bashi, and kasasagi-bashi, 鵲橋, magpie-bridge. The kasasagi/magpie is black and white, and some species have blue plumage. In most old illustrations of the Tanabata scene, the birds are black.

Altair and Vega together with Deneb form the Summer Triangle, Natsu no Dai-san-kaku, 夏の大三角, Summer’s Great-three-corner. The star Deneb is called Ama-no-hashi-date, 天橋立, Heaven-’s-bridge-stand. Deneb is the ‘tail’ of the constellation Cygnus, which in Japanese is Haku-chō, 白鳥, White-bird, swan, as its name indicates, is white. The bridge of magpies seems contrary as the magpie is black, and Cygnus is white.

And so, why the magpies? Were they ever crows? The birds are identified as kasasagi. Crows and magpies are believed to take souls to heaven. The Tanabata bridge for the cow-herder man and the weaver princess is made of magpies. In Japanese lore, there is great importance upon hearing the ‘hatsu garasu’, first [cawing of the] crow. Raving raven? One of my favorite ‘words’ comes from Hamlet – “croaking raven,” perhaps meaning ‘crow king raven’.

In 589, Shō-toku Tai-shi, 聖徳太子, Holy-virtue Grand-child (Prince), built a shrine to honor his parents, and to worship the Shi-ten-nō, 四天王, Four-heaven-gods. It was constructed in a forest near Ōsaka town, and called it Nan-bu no Mori, 難波の杜, Turbulent-wave ’s Shrine. The Kanji, nan-bu, 難波 is also read Nani-wa, which was the name of the capital before it was named Ōsaka.

Shōtoku sent Empress Sui-ko, 推古, Conjecture-old, on a peace mission to Silla in Korea, and she returned with a pair of magpies. Shōtoku then renamed the shrine Kasasagi Mori no Miya, 鵲森の宮, Magpie Forest ’s Palace.

A species of magpie in eastern Asia were kept because of their melodic song. The relevance is the reference to the magpie at that early date. The Chinese has observed the magpie bridge and the stars of Tanabata for centuries before the time of Shōtoku. There are later remnants of the Kasasagi shrine, and the surrounding area is known as Mori-no-miya. Shi-ten-nō-ji, 四天王寺, Four-heaven-kings-temple, is the earliest Buddhist temple in Japan.

In Shōtoku’s lifetime, near the entrance of Shitennōji, were the shrines of Ō-tori-i, 大鳥居, Great-bird-reside, Tama-tsukuri Ina-ri Jin-ja, 玉作稲荷神社, Jewel-make Rice-carry God-shrine, and Kasasagi Mori no Miya. The Shintō gate, tori-i, means ‘bird-reside’, and the bird is said to be the chicken, which is sacred to Ama-terasu, 天照, Heaven-brightener, the Sun Goddess. Although very remote, the bird of the torii might be the kasasagi. The torii is a kind of bridge separating and joining two worlds.

Tanabata may also have origins in the Taoist illustration of the Dai-kei-zu, 内経図, Inner-warp-picture. The Chinese Neijing Tu is a Taoist ‘inner landscape’ diagram of the human body and the mechanism and the workings of the kundalini. The weaver woman (princess) is working an ito-kuri-guruma, 糸繰車, thread-turn-wheel, making thread.

The Oxherd is pictured above her touching the constellation of the Big Dipper. Of note in the lower area of the landscape is man leading an ox plowing a field; it might appear that he is the Ox Man of legend, however, the text accompanying the image describes this as “the iron ox ploughs the field where coins of gold are planted.”

In the upper sphere, Lao-tzu, 老子, Elder-child, sits regally, and beneath him is Da-ruma, 達磨, Attian-polish. The green ‘river’ flows upward from the base of the spine to the brain, with major incidents along its route.

Kaji no ha, 梶の葉, paper mulberry-leaf; (Broussonetia papyrifera). The leaf of the paper mulberry tree is so important to Japanese culture that the old name for the eighth month is Ha-zuki, 葉月, Leaf-month, which is derived from kaji no ha, 梶の葉, paper mulberry’s leaf. There is a phrase: Ha-zuki kaji no ha, 葉月梶の葉, Leaf-mon paper mulberry’s leaf. The Kanji for kaji, 梶, is composed of ki, 木, tree, and o, 尾, tail.

The poems and prayers written on tanzaku, were originally written on a kaji no ha, 梶の葉, paper mulberry leaf. The inner bark of the kaji has been used in making paper in Japan for centuries. On the morning of the seventh day, dew is gathered from the leaves of the lotus or elephant ear plant to wet the suzuri, 硯, inkstone, for writing on the leaves or tanzaku. Dew, tsuyu, 露, comes from heaven, and is returned in the form of a prayer.

The Kanji, 梶, also means oar, the wooden device used to move a boat. Perhaps there is some remote association with one’s getting to Jō-do, 浄土, Pure-land paradise of A-mi-da Nyo-rai, 阿弥陀如来, Praise-increase-steep Like-become. One must cross a great body of water, and the easiest way to get there is taking a boat. The halo behind Amida is in the shape of a boat.

A popular Tea presentation in the summer months is called ha-buta, 葉蓋, leaf-lid, when a leaf is used as a lid for a slender hoso-mizu-sashi, 細水指, narrow-water-indicated. Its origin began when Rikyū put a leaf over the water in the chō-zu bachi, 手水鉢, hand-water bowl, in the garden, ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground, to shade it from the heat of the sun. The preferred leaf for the mizusashi is the kaji no ha, 梶の葉, paper mulberry-leaf. Part of the stem should be retained to poke into the leaf when it is folded after use, and put into the ken-sui, 建水, build-water.

Gen-gen-sai, 玄々斎, Mystery-mystery-abstain, XI Iemoto of Urasenke, used the otoshi, 落とじ, the water and flower container of the sue-hiro kago, 末広籠, ends-wide basket. He had the cylindrical mage-mono, 曲物, bent-thing, made of cedar, lacquered black with patches of gold leaf, and used it as a mizusashi. Although followers of Chanoyu enjoy using Gengensai’s mizusashi, any suitable vessel may be used with the habuta.

The suehiro kago is often used to display the aki no nana-kusa, 秋の七草, autumn’s seven-grasses, which begin to bloom in August. The aki no nanakusa have their counterpart in the haru no nana-kusa, 春の七草, spring’s seven-grasses. These are young nourishing herbs pounded and beaten into a rice gruel, nana-kusa gayu, 七草粥, seven-grasses gruel, and eaten on the morning of the seventh day of the New Year.

August 7 is Ri-sshu, 立秋, Start-autumn; 24 seasonal divisions of the solar year. Start of the lunar seventh month, Saru no Tsuki, 申の月, Monkey’s Month. The Kanji for autumn, aki, 秋, is composed of ine, 禾, grain, and hi, 火, fire, as the heat of summer and early autumn has caused crops to ripen. The dragonfly, especially the aka-tonbo, 赤蜻蛉, red-dragonfly, as in the photograph, is an emblem of the start of autumn.

The first event of Obon is the mukae-bi, 迎え, welcome-fire, when fires are lit in front of the home to welcome the spirits of ancestor returning from paradise. The last event is okuri-bi, 送り火, send-fire, which are again fires set before the home to escort departed spirits back to paradise. One of the most magical events is tō-rō nagashi, 灯篭流し, lamp-basket flow, when candles in floating lanterns, set on rivers that flow to the sea, and ultimately back to the Ama-no-kawa, 天の川, Heaven-’s-river, the Milky Way.

The origins of the hōroku may be found in part in the un-fired clay lid of the Raku, 楽, Pleasure, kiln. Firing in a Raku kiln may only take a few hours, and when the lid is sufficiently fired, the kiln is opened. As the lid cannot be re-used, a number of them are created, and were put to good use elsewhere, such as in the kitchen.

The welcome and farewell bon fires are made in a hōroku, which is also used in the dairo season to hold sumi dō-gu, 炭道具, charcoal-way-tool. At Mi-bu-dera, 壬生寺, North northeast-life-temple, prayers and blessings are written on multiple hōroku that are stacked up and pushed over to be destroyed.

August 12 is Kyū Bon, 旧盆, Old Tray, when spirits of the dead return to their homes during the full lunar seventh month.

In Japan, Buddhist rites for departed spirits are held in a festival called O-bon, お盆, Hon.-tray. Obon is more popularly observed in July from the 13th to 16th, when millions of people return to their ancestral homes. It is the second most observed festival in Japan. July is summer. The true Obon is a lunar event occurring on the fifteenth day of the seventh moon, which is in August, and in Japan, August is autumn. In traditional Asia, according to the solar calendar autumn begins on August 7th, Ri-sshu, 立秋, Start-autumn. Obon is an autumn festival. In the year 2022 the true traditional Obon occurs on August 13.

In China, it is believed that on the days of Ki-zuki, 鬼月, ‘Ghost’ Month, and especially on the night of the full moon, there is more of a bridge between the dead and the living, so they must take precautions or honor the dead. They perform ceremonies or traditions to protect themselves from attacks or pranks by the ghosts and to honor and worship their ancestors or famous people of the past. It is believed that the ghosts of dead people can help and protect them.

This Buddhist festival has been celebrated for more than five hundred years. It originates from the story of Maudgalyayana and/or Mogallana, in Japanese is Moku-ren, 目連, Eye-connect. He was one of Buddha closest disciples, who used his powers to see the spirit of his deceased mother. He discovered she had fallen into, and was suffering in the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, one of the Six Realms of Existence called the Roku-dō, 六道, Six-ways. There are six manifestations of Jizō, Roku Ji-zō, 六地蔵, who dwell in the Six Realms.

He offered her food which burst into flames. The Buddha advised him to make offerings to the Buddhist community that transferred the merits to her. On the fifteenth day of the seventh month, he followed Buddha’s advice, and his mother was released from her suffering. Mokuren danced with joy which is the origin of the Obon dance.

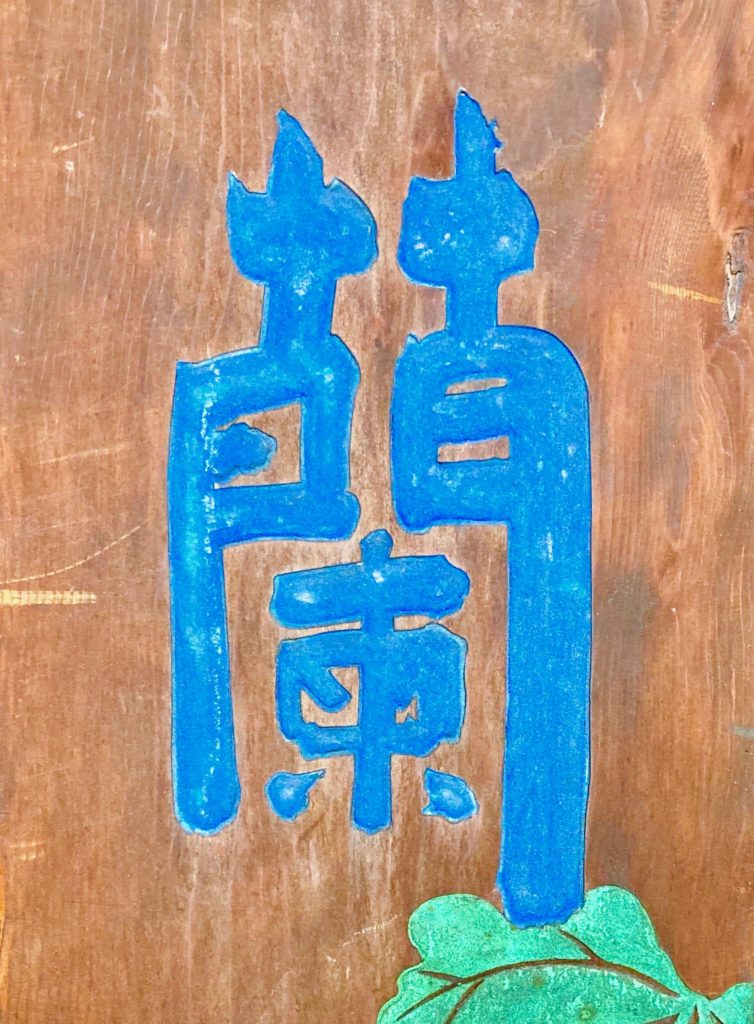

Kan-ban, 看板, show-board, cedar wood shop sign with carved and painted motifs and characters; Ga-ran-dō, 伽蘭洞, Attend-orchid-cave. Detail: ran, 蘭, orchid; is a character that is part of the full Japanese name for Obon.

O-bon is a contraction of U-ra-bon, 盂蘭盆, Bowl-orchid-tray, which is derived from the Sanskrit word ‘ullambana’, meaning ‘hanging upside down’. The Kanji ra also ran, 蘭, orchid, is also written with the Kanji, 蘭. The Kanji 蘭, without the grass radical, kusa, 艹, is the Kanji ran, 闌, rise high, well along. The Kanji is also read takeru, takenawa, tesuri, as in the height of summer, party, in full swing, etc. The word ‘takenawa’, is also written with the Kanji, 酣, with the same meanings. The Kanji is composed of sake and sweet. The Kanji ran/takenawa, 闌, is composed of mon, 門, gate, and kan, 柬, pick, choose, and/or tō, higashi, 東, east. The Kanji included with mon/gate makes considerable difference in the meaning. The word ‘takenawa’ also has the meaning of take-nawa, 竹縄, bamboo-rope. ‘At the height’ or ‘extreme of’ would surely apply to the height of ‘summer’, although Obon is traditionally in autumn.

In the Buddhist underworld, departed spirits are hung upside-down over food laid out on tables just out of their reach, creating the torture of hunger. One of the main features of Obon is offering foods, and welcoming the spirits to join the family at meals. ‘Festival’ is the appropriate word for Obon, as the word comes from Middle English via Old French from medieval Latin festivalis, from Latin festivus, from festum, (plural) festa ‘feast’.

In China, the Obon festival is called the Feast of Lanterns. U-ra-ban-kyō, 盂蘭盆経, Bowl-orchid-tray-sutra, known in English as the Ullambana Sutra. The sacred text relates of the participation of Ji-zō Bo-satsu, 地蔵菩薩, Earth-keep Sacred tree-buddha, savior and guardian of the world until the arrival of the Future Buddha, Maitreya, Mi-roku Bosatsu, 弥勒菩薩, Increase-manage Sacred tree-buddha.

For Obon, in some traditions, ‘lanterns’ are hung from asa-nawa, 朝縄, hemp-rope, that is tied between two stalks of bamboo. This rope acts as a barrier that keeps evil away. There are more than a dozen ways of writing hōzuki, including the most familiar Kanji, 酸漿, bitter-drink.

A more complete altar for Obon has four bamboo stalks to create a square. In Shintō, the shi-me-nawa, 注連縄, flow-along-rope, delineates a square that is sanctified. The rope that is tied from bamboo to bamboo is made of twisted hemp fibers with hemp fibers and shi-de, 四手, four-hand, paper streamers, suspended from it.

There is some belief that the bon-dana should be placed in the west facing east, so that when praying in front of the altar, one is also facing west and the Goku-raku Jō-do, 極楽浄土, Extreme-pleasure Pure-land of Amida. This is where the ancestors’ spirits reside, so that the bamboo gate is where the spirits would enter through the altar. The ancestors will go back and forth to the world of Goku-raku Jō-do, 極楽浄土, Extreme-pleasure Pure-land.

A kind of cucumber, kyū-ri, 胡瓜, foreign-melon, and an eggplant, na-su, 茄子, eggplant-of, are included in the offerings of O-bon,お盆, Hon.-tray, The vegetables are mad into animals: a kyū-ri no uma, 胡瓜の馬,foreign-melon’s horse, and na-su no ushi, 茄子の牛, eggplant-of ’s ox. The kyūri/cucumber is made into an uma/horse for a quick arrival of spirits from paradise, and a nasu/eggplant into an ox for a slow return to paradise. It is curious that the eggplant is present at the New Year, and near the beginning of the second half of the year. New Year’s dream: hatsu-yume, 初夢, first-dream: ichi-fuji ni-taka san-nasubi, 一富士 二鷹 三茄子, one noble-gentleman, two-hawk, three-eggplant-of. These are wordplay on no-second, in-high, three-bear-child.

Uma means horse, as well as to give birth, life. Nasu means eggplant and to bear (young). Uri means melon and to sell. Ushi means ox, cow, and back. The Japanese word for eggplant is nasu, which is wordplay on nasu, 成す, to become, 為す, to become, 生す, to live, 済す, to conclude, finish.

The eggplant, nasu, from the Nara period has been associated with women, especially brides, and there is an expression that states that a bride should not eat autumn eggplants “because they are too delicious.” Perhaps there is a correlation between the Star Boy and the kyu-uri, 胡瓜, foreign-melon, cucumber (Cucumis sativus) , as the uri is one of the offerings. The nasu and the uri are among the offerings because they float on water which is identified with the River of Heaven, and is connected with the purification of water. Hence, one should not eat the eggplant and melon offered at Tanabata, as they have taken impurities from the water.

The word ushi for ox or cow, is also written, 丑, which refers to the Asian zodiac sign of the Ox. The sign also is the time between 1am and 3am, the north-northeast. The word uma for horse, is also written, 午, which is the Asian zodiac sign of the Horse. The sign is the time between 11am and 1pm – noon is shō-go, 正午, Correct-horse.

In Kyōto, for Obon, on the night of August 16, great fires are lit on the sides of five mountains located around the city: Go-zan no Okuri-bi, 五山送り火, Five-mountain Send-fire. The fires in containers are arranged to form Kanji and depictions of a boat and a torii.

The most prominent and perhaps the most iconic fire is Dai-mon-ji, 大文字, Great-character-letter, to the east of the capital. So revered is this event that the mountain, Nyo-i-ga-take, 如意ヶ嶽, Like-mind-’s-peak, is named for the character-fire, Dai-mon-ji-yama, 大文字山. The word ‘nyo-i’ is associated with the hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel, and is called the Nyo-i-hō-ju, 如意宝珠, the ‘wish-granting-treasure-jewel’, which is identified with Kannon and Jizō, and others.

According to Buddhist traditions, O-bon, お盆, Hon.-tray, is a festival in mid-summer when lanterns are hung in front of houses to guide the ancestors’ spirits home, Obon dances are performed, graves are visited and food offerings are made at home altars and temples. At the end of Obon, floating lanterns are put into rivers, and seas in order to take the spirits back into their world.

The word ‘bon’ has another important meaning in Buddhism. Bon, 凡, ordinary, common, etc. Bon-sō, Bon-zō, 凡僧, Ordinary-priest, monk, unranked Buddhist priest. The origin of the English word ‘bonze’ refers to a Buddhist priest or monk. Another Japanese word ‘bon’ refers to the Kanji, 梵, meaning Sanskrit, purity, ancient Indian culture, and Buddhism, in general.

The word ‘bon’ in ‘bonfire’ rhymes with ‘bond’, and not ‘bone’ as its supposed origin. Bonfires, originally lit as part of midsummer celebrations, were not generally associated with the burning of bones. However, the first edition of the OED (under the title A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, 1887) stated that “for the annual midsummer ‘banefire’ or ‘bonfire’ in the burgh of Hawick [in Roxburghshire, Scotland, old bones were regularly collected and stored up, down to c. 1800.” The source of the word ‘bon’ is from Middle English ‘ban’ as in to banish, to summon, to curse, etc., although the pronunciation of ‘a’ is closer to barn.

August 23 marks Sho-sho, 処暑, Limit-heat; one of the twenty-four seasonal divisions of the solar year. The mid-point of the lunar month of the Monkey, Saru, 申. The sign of Saru is joined with the sign of Hitsuji, 未, Ram, and together create the sign of Hitsuji-Saru, 坤, Ram-Monkey. This Kanji is also read Kon, and is one of the eight trigrams of the Eki-kyō, 易経, Change-sutra. This sign is protected by Dai-nichi Nyo-rai, 大日如来, Great-sun Like-become. In the yo-jō-han, 四畳半, four-mat-half, Tearoom, according to the Eki-kyō, Dainichi is located in the southwest corner, and the cha-dō guchi, 茶道口, tea-way door, that is used by the teishu.

On August 24 Ji-zō Bon, 地蔵盆, Earth-keep Tray; there are Buddhist rites especially held for children in remembrance of departed spirits, with Jizō as a special guardian. Jizō helps the souls of children cross the San-zu no Kawa, 三途の川, Three-crossing’s River, in the underworld.

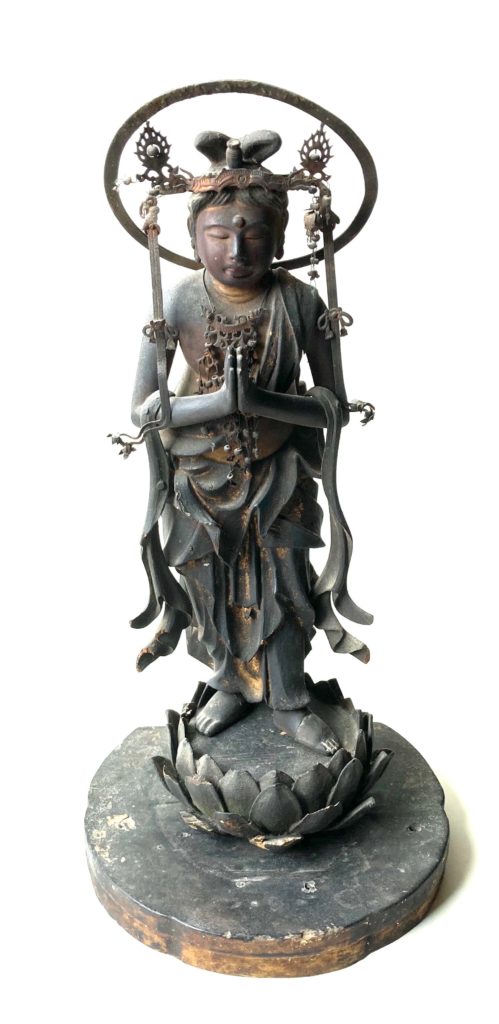

Jizō, guardian of the world until the arrival of Maitreya, the Buddha of the future, is manifest in each of the Roku-dō, 六道, Six-ways, the six realms of the Buddhist world of existence.

When a Buddhist dies, it is hoped that Amida Nyorai will come to welcome one’s spirit, and guide it to his golden paradise in the west called Goku-raku Jō-do, 極楽浄土, Ultimate-pleasure Pure-land. The approach of Amida is called Rai-go, 来迎, Become-welcome, and he is accompanied by Sei-shi Bo-satsu, 勢至菩薩, Strength-attain Grass-buddha, on his right side, and Kan-non Bo-satsu, 観音菩薩, See-sound Grass-buddha, on his left side.

At times, Amida is accompanied by Jizō Bosatsu on his right side, and Kannon Bosatsu still at his left side. In the picture, Amida is depicted with his right hand toward the earth in a gesture of welcome, and perhaps a lotus on his left hand upon which one is reborn in his paradise. Kannon holds a wish-granting nyo-i, 如意, as-desire, scepter in the right hand, and un-recognizable object in the left hand. Of particular note are the faces of dragons above the heads of Jizō and Kannon.

The manji, 卍, swastika, on Amida’s chest has the ends indicating that it would turn clockwise. In Buddhism, this is symbolic of compassion and mercy, whereas its counterpart is depicted as it would turn counter-clockwise, which is symbolic of learning and practice. The manji of leaning and practice can be identified with the pattern of the tatami of the yo-jō-han, 四畳半, four-mat-half, of Dō-jin-sai, 同仁斎, Equal-benevolence-abstain, of the Tō-gu-dō, 東求堂, East-request-hall, of Gin-kaku-ji, 銀閣寺, Silver-pavilion-temple, the first yojōhan room for serving Tea.

Jizō is depicted holding a shaku-jo, 錫杖, tin-staff, in his right hand, and hō-ju, 宝珠, treasure-jewel in his left hand.