May Days of Chanoyu

The start of May in Japan is a busy season with many celebrations at the beginning of the month. Go–gatsu, 五月, Five-month, May, is also referred to as Sa-tsuki, 皐月, Rice planting-month as well as ta-ue, 田植, paddy-plant. From April 29, former Emperor’s Birthday, to May 5, Tan-go no Se-kku, 端午の節句, Edge-horse’s division-phase is called ‘Golden Week’.

1st Hachi-jū-hachi-ya, 八十八夜, Eight-ten-eight-night, mid-time of 21 days of cha-tsumi, 茶摘み, tea-pinch. Tea picking begins on April 21 in 2025.

3rd Ken-pō-ki Nen-bi, 憲法記念日, Constitution-law-account Desire-day, Constitution Day.

4th Midori no Hi, 緑の日, Green’s Day, former Emperor Hirohito’s birthday.

5thTan-go no Se-kku, 端午の節句, Edge-horse’s division-phase. It is Ri-kka, 立夏, Start-summer.

The 5th of May is also Ko-domo no Hi, 子供の日, Child-accompany’s Day. Lunar 5/5 in 2025 is on solar June 1st .

The start of May, in 2025, is hachi-jū-hachi, 八十八, eight-ten-eight, 88, which can also be written as the Kanji for kome, 米, rice, which represents infinity in all directions. Adding the radical for kusa, 艹, grass, creates the Kanji for cha, 茶, tea: tea is omnipresent. The Kanji, 艹, is also the number for ni-jū, 十十, ten-ten, meaning 20. 20 added to 88 is 108, hyaku-hachi, which is the number of carnal desires, bon-nō, 煩悩, that must be dispelled. Many names of various matcha include the word, mukashi, 昔, past, which is also the number ni-jū-ichi, 21, and nichi for days, or 21 days, the same as the number of days for tea-picking.

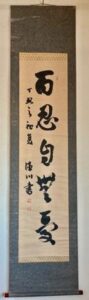

Garandō with utensils for early summer usu-cha, 薄茶, thin-tea. Tokonoma: kakemono, ‘百忍自無憂’; hanging hanaire, stoneware tsutsu; hexagonal kōgō, on pack of kami kama-shiki. Furo/kama on an ōita, with hishaku and gotoku futaoki; Shino mizusashi; ‘flurry’ usu-ki; porcelain sometsuke chawan containing chashaku, chakin, and chasen; bronze kensui.

Hyaku-nin ji-mu-yu, [hyaku-nin onozukara urei nashi], 百忍自無憂, Hundred-endurances self no distress,

Inscribed and signed Hinoto-ushi sho-ka, 丁丑初夏, Fire young brother-ox First-summer, (1937), Toku-gawa fude, 徳川筆, Virtue-river brush. Sho-ka, 初夏, refers to the fourth month of the lunar calendar.

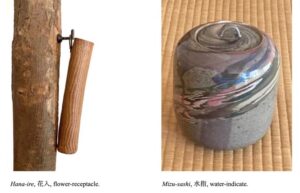

Kake-hana-ire, 掛花入, hang-flower-receptacle, stoneware tsutsu, 筒, cylinder, neri-komi, 練り込み, knead-mix, different clays are layered together; L. 6.3 sun kane-jaku, by Makoto Ya-be, 誠矢部, Truth Arrow-guild, Boxford. With a metal hanger. The hanaire is hanging on the toko-bashira, 床柱, floor-post, which is the trunk of a katsura, 桂, cinnamon bark.

Mizu-sashi, 水指, water-indicate, stoneware ‘natsume’, 棗, jujube, covered vessel, neri-age, 練り上げ, knead-up, different clays blended and combined together; H. 5.8 sun kane-jaku, by Makoto Ya-be, 誠矢部, Truth Arrow-guild, Boxford, Mass.

Kō-gō, 香合, incense-gather, ro-kkaku, 六角, six-corner, black lacquered wood with red lacquered interior with design of tsukushi, 土筆, earth-brush, horsetail; L. 2.7 sun kane-jaku, with three pieces of byaku-dan, 白檀, white-sandalwood. Sandalwood, which is sacred to Buddhism, is burned in the furo.

Two versions of the tori-awase, 取り合わせ, take-gather, the assembly of different utensils for a Tea presentation.

The difference in the dōgu toriawase was the choice of usu-ki, 薄器, thin-container. The original selection was the vermillion-lacquered ya-kki, 薬器, medicine-container, Its distinctive form and bright color seemed in conflict with the elaborate design elements and intense color. Therefore, the simple and plain black-lacquered usuki called fu-buki, 吹雪, blow-snow, was chosen as a replacement.

Ki-men fu-ro/kama, 鬼面風炉/釜, dragon-face wind-hearth/kettle, bronze and iron, displayed on an ō-ita, 大板, large-board, black-lacquered wood; 14 sun kane-jaku square. Different Tea Masters had ōita of different sizes. Sen Hō-un-sai, 千頬雲斎,Thousand Phoenix-cloud, designed an ōita that measured 14 x 12 sun kane-jaku. Other choices had boards that were also not square. The ōita pictured above is made of the plywood board cut from the ‘table’, which made the opening for the ro.

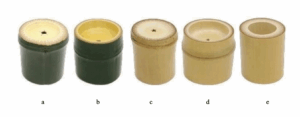

Bamboo futa-oki, 蓋置, lid-place; height of each is 1.8 sun kane-jaku. A freshly-saw cut green bamboo futaoki is called hiki-kiri, 引切, draw-cut. The hole, with five points, in the fushi, 節, node, septum, changes the nature of the bamboo from a container, In, receptive, to a support, Yō, positive. Also it helps to release the lid from the suction of the wet bamboo.

(a) ao-dake, 青畳, green-bamboo, moto-bushi, 元節, origin-node, also called ten-bushi, 天節, heaven-node, used with for fu-ro, 風炉, wind-hearth.

(b) Green bamboo naka-bushi, 中節, middle-node, used with ro.

(c) Similar to (a) but of aged bamboo.

(d) Similar to (b) but aged bamboo.

(e) Fushi-nashi, 節無し, node-not, also called fuki-nuki, 吹抜, blow-out, wa, 輪, ring, used with furo and ro. The wa futaoki is believed to be the original form of the futaoki, and made of bronze.

There is the theory that a new futaoki is made of ao-dake, 青竹, green-bamboo, is to be used for the first use of the fu-ro, 風炉五徳, wind-hearth, in that season, called sho-bu-ro, 初風炉, first-wind-hearth. The same is true with ro, and a new aodake nakabushi futaoki is cut or acquired for the first use of the ro in that season, which is called ro-biraki, 炉開き, hearth-open. The same futaoki would be used throughout the season, aging, and changing color from green to ‘white’. Hence the use of an aged ‘white’ bamboo futaoki used during the 10th month, at the end of the furo season. In practice, however, people generally cut or acquire a new aodake futaoki when presenting Tea. The green bamboo futaoki is, ideally, cut from fresh bamboo just prior to its use, and kept in water, like a cut flower. In effect, it is still alive, but will die, being symbolic of the evanescence of life.

To make a futaoki, the bamboo stalk is cut so that the root end is upward, which causes the growth direction of the bamboo futaoki to be upside down. This changes the futaoki from Yō to In, and the hole changes it from In to Yō. Several types of objects, like the gotoku, are inverted to become a futaoki.

A bamboo futaoki is generally used in a Tea presentation when the mizu-sashi, 水指, water-indicate, is placed directly on the tatami floor. When the mizusashi is displayed on a stand, tana, 棚, shelf, or a board, ita, 板, a futaoki other than bamboo is used. One exception is an aged bamboo futaoki that bears a design or the ka-o, 花王, flower-seal, of a Tea master or Buddhist priest

Futaoki, wa, 輪, ring, cream-colored ceramic, with color and gold glaze design of sasa, 笹, bamboo grass, part of a set of kai-gu, 皆具, all-tools, Kyō-yaki, 京焼, Capital-fired, pine tree design, used for both furo and ro. The word sasa, 笹, bamboo grass, may be wordplay on sasageru, 捧, to give; to offer; to consecrate.

Go-toku, 五徳, five-virtues, Kara-kane, 唐銅, Tang-copper, bronze used for both furo and ro.

Ho-ya gō-ro futa-oki, 火舎香炉蓋置, Fire-house incense-hearth lid-place, bronze, with invertable lid, and five dragon talons. This futaoki is of primary use in a very formal Tea presentation named Gyō, 行, Transition, which identifies the function of each Tea utensil. The five talons, tsume, 爪, correspond with the five cuts of the bamboo futaoki ‘star’ aperture.

There is a general rule for a Tea presentation using an ao-dake futa-oki, 青竹蓋置, green-bamboo lid-rest, if the mizu-sashi, 水指, water-indicate, is placed directly on the tatami: hakobi mizu-sashi, 運び水指, carry water-indicate. According to tradition, there are exceptions. In the rustic nature of the 10th month, aged bamboo is used for the futaoki. Rikyū preferred that the height of the futaoki should be 1.8 sun kane-jaku.

Because the futaoki is placed directly on the ōita, some masters prefer to use an aged bamboo futaoki, as green bamboo is damp. Some masters use an aged bamboo futaoki that bears a design or a ka-ō, 花押, flower-seal. Others use a ceramic futaoki. When the kama sits directly on the furo, a trivet-like go-toku, 五徳, five-virtues, is not needed, a go-toku futa-oki was Rikyū’s choice.

Mizu-sashi, 水指, water-indicate, ceramic vessel, hitoe-guchi, 一重口, one layer-opening, slightly tapered cylindrical form with irregular, thick, white glaze over dark line drawing, Shi-no yaki, 志野焼, Aspire-field fired, by Yama-guchi Masa-fumi, 山口正文, Mountain-opening Correct-letter; H. 5 sun kane-jaku. With a slightly oval, black lacquered wooden lid, with an arched half-loop handle. Yamaguchi Masafumi, 1941-2018, was the 5th generation of the Nishi-yama kama, 西山窯, West-mountain kiln, Se-to-shi, 瀬戸市, Rapids-door-city, Ai-chi-ken, 愛知県, Love-know-prefecture.

Utensils for a traditional annual event such as a memorial are generally the same for each Tea presentation. Variations are likely. The kakemono is usually the same for a specific occasion is traditional, such as the memorial for Rikyū-ki, 利休忌. The culture of Japan is based on tradition, which is den-tō, 伝統, transmit-origin. Generation after generation adhere to the inherent customs and procedures known by their tradition.

Deviating from the tradition is acceptable provided there is a continuation of the objects or procedures that continue to be followed. The ceramic works of Raku are an example of continuing their making of traditional chawan and other familiar utensils, in addition to contemporaneous styles and tastes of their society.

Some Tea utensils are famous and highly prized because of their history or who owned them. A chaire is a chaire. Does the costly utensil make better tea than another of no fame? Rikyū’s very name alludes to this in his name, 利休, rich-quit, which is based on the adage, ‘Mei ri tomo kyū’, 名利共休, Name riches both leave, fame and fortune are fleeting.

Rikyū followed traditions and at the same time took objects that were suited to the task at hand. A seed storage jar from the kitchen was used as a mizusashi when presenting Chanoyu. If it works – use it. The costliest object or an object made by a famous maker does not necessarily improve its function. There are chawan that may so ill-formed that they are truly unusable, should not or ought not to be used.

The following is from “The Ten Ox-herding Pictures” by Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki.

Picture IX. Returning to the Origin, …… “The waters are blue, the mountains are green; sitting alone, he observes things undergoing changes. To return to the Origin, to be back at the Source—already a false step this! Far better it is to stay at home, blind and deaf, and without much ado; Sitting in the hut, he takes no cognizance of things outside, Behold the streams flowing-whither nobody knows; and the flowers vividly red – for whom are they?”

This passage contains the familiar Japanese phrases; Sei-zan Ryoku-sui, 青山緑水, Blue-mountain Green-water. Also the latter part of ‘yanagi was midori hana kurenai’, 柳緑花紅, willow green flower red.

From left: hako, 箱, box, hinoki, 檜, cypress, with attached sa-na-da himo, 真田紐, true-field ribbons; L. 7.8 sun kane-jaku: with signed lid. Signed tomo-zutsu, 共筒, together-cylinder, take, 竹, bamboo, with calligraphy; L. 7.2 sun kane-jaku. Cha-shaku, 茶室, tea-scoop, mottled take, 竹, bamboo, naka-bushi, 中節, middle-node; L. 6 sun kane-jaku.

Cha-shaku, 茶杓, tea-scoop; bamboo naka-bushi, 中節, middle-node, by Kage-bayashi Sō-toku, 影林宗篤, Shadow-grove Sect-kind, named ‘Hō-rai’, 蓬莱, Mugwort-goosefoot, Matsu-naga Gō-zan, 松長剛山, Pine-long Strong-mountain, abbot of Kō-tō-in, 高桐院, High-paulownia-sub temple, Dai-toku-ji, 大徳寺, Great-virtue-temple, Kyōto.

Tomo-zutsu, 共筒, together-cylinder: from top, inked with a shi-me, X, seal, brushed on the join of lid and tube; ‘蓬来’, Mugwort-goosefoot; brushed ka-ō, 花押, flower-seal, stylized number of ancestral generation. Box lid: Kanji for name, ‘蓬来’, signed Murasaki-no Kō-tō Gō-zan, 紫野高剛山, Purple-field High-paulownia Strong-mountain.

Hōrai is also the name of the eight-mat cha-shitsu, 茶室, tea-room, in Kōtōin, which is derived from the mythical island of Hō-rai-san, 蓬来山, Mugwort-goosefoot, where lives the Immortal Sages and the Shichi-fuku-jin, 七福神, Seven-fortune-gods.

Cha-wan, 茶碗, tea-bowl, porcelain, underglaze blue some-tsuke, 染付, dye-attach, in the style of Shon-zui, 祥瑞, Fortune-congratulation, Kiyo-mizu-yaki, 清水焼, Pure-water-fired, by Fuji-ta Zui-ko, 藤田瑞古, Wisteria-field Auspicious-old; diam. 4 sun kane-jaku, 20th century, Kyōto. Word of caution: porcelain bowls containing tea can be very hot to the touch, so extra care must be taken in tempering the hot water.

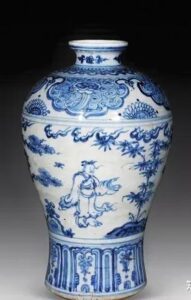

The Chinese porcelain ‘mei-ping’, 梅瓶, ‘plum’-bottle, some-tsuke, 染付, dye-attach, was made in mid-Ming, 17th century. The vase was originally a wine bottle used to display flowering ‘plum’ branches, ume no hana, 梅の花, bai-ka, 梅花, ‘plum’s flower, Beginning in the Tang dynasty, in its simplicity, it is one of the origins of cha-bana, 茶花, tea-flowers, where a single flower represents the entire natural world. Ume-shu, 梅酒, ‘plum’-alcohol, made with green ‘plums’, has been cherished and consumed for its medicinal benefits in China over 3,000 years ago, and was introduced to Japan in the 10th century.

For further study, see also: May: Still Following Elephants, Tea in May, Buddha’s Gems: Chaki and Chanoyu, and Go-Gatsu